When I was at Forum for the Future, I tried to design futures projects that would help people to make better decisions. ‘Better’ as in, decisions that in the long term would contribute to, and not erode, human wellbeing and the living world. Sometimes the results felt transformational, sometimes they were disappointing. Whenever the process worked, it was because the people we coached through the process changed the way they thought about the world – if only for the duration of the project.

I remember a client telling me once, that the work had made him much more aware day-to-day of changes taking place in the world around him and how those might play out in the future. He became a habitual spotter of weak signals, thinking about what they might be weak signals of. This connected him into a much broader landscape than he was normally conscious of. And he said that had changed the way he prioritised and made decisions.

This is a kind of power. Using different futures tools and methods to inquire into the world and how it is changing, you end up taking a little more control over the future.

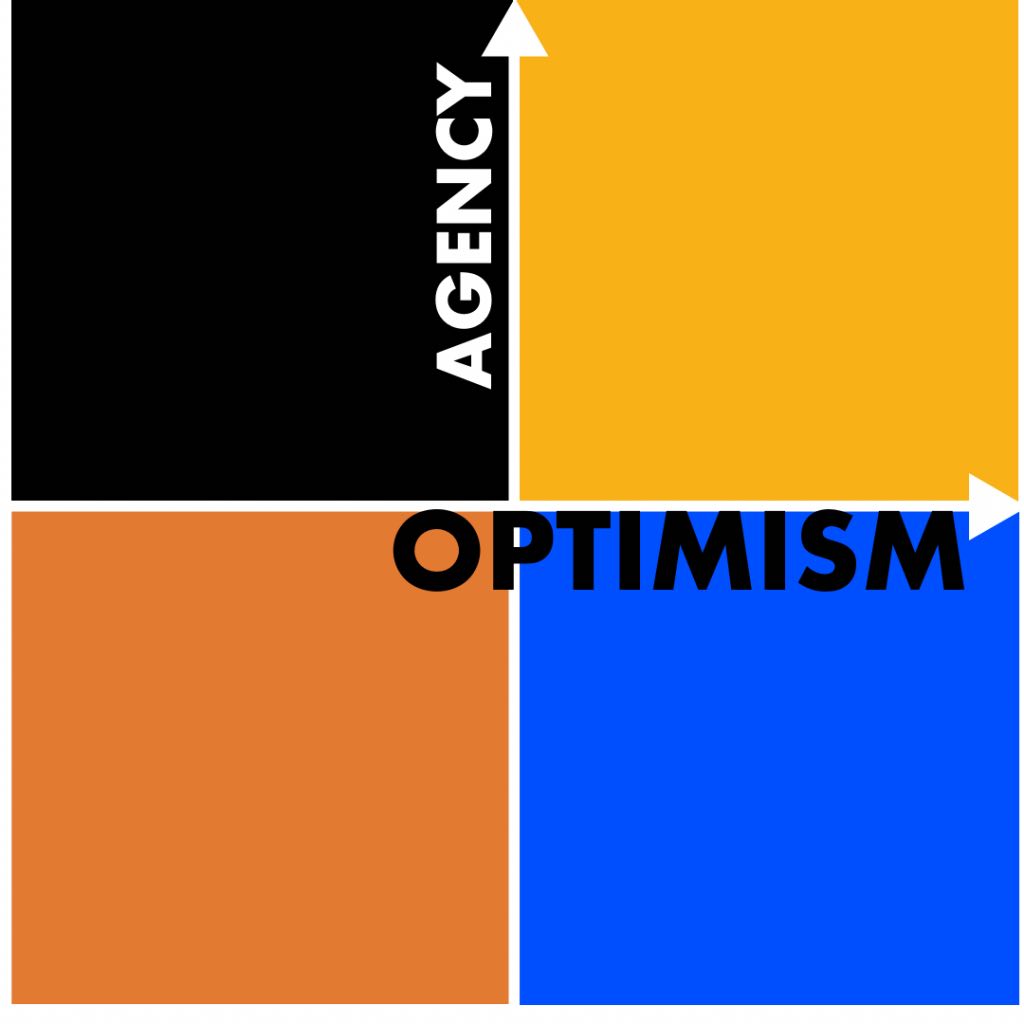

You can assume more agency, gain a positive focus – not quite optimism, more like a willingness or a motivation to engage, and a sense that you are not powerless in the face of immovable things.

You really get a flavour of this if you play the Polak game, a quick and fun futures exercise originating in the work of the Dutch sociologist Fred Polak. I was introduced to this game in a workshop run by the futurist John Sweeney, and have used it lots since. There are three simple steps in the game.

First you ask people to stand somewhere on a line based on how optimistic or pessimistic they feel about the future. Standing at one end of the line means they are very optimistic, at the other end very pessimistic.

Next you ask people to imagine another axis in the room bisecting the first, which describes whether they feel agency over the future or if they feel helpless to influence it. Without shifting where they are on the first axis, they move along the second axis. You end up with the room in four quadrants. People in the first quadrant are optimistic and feel agency, those in the second are optimistic but feel they have no power to influence the future. The third quadrant contains people who are pessimistic yet feel they can influence things, and the final quadrant is where those who feel pessimistic and powerless stand. In the final step of the game you have fun by getting the people in each quadrant to form a team, try to justify their choices and convince others to join them. Whichever team recruits the most new members wins.

When I have played this game, I’ve used it as a warm-up at the start of a futures workshop. Then at the end, after having talked about futures and patterns of change and possible scenarios all day, I’ve repeated the first two steps of the Polak game. Each time, there have been more people in the positive/agency quadrant than there were before. The sense of agency in the room had increased: people felt more powerful after a day of futuring.

I saw something similar happen in Plymouth in a project run by The Alternative UK for Local Trust (where I work now) in May 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was at its most intense. In three separate sessions over a couple of weeks, Indra Adnan and Pat Kane steered a group of community activist Plymothians through a futures conversation, moving from how people felt about the pandemic, to how it was affecting their community and what it might mean for their futures. Indra and Pat referred to the Long Crisis scenarios – which describe possible futures after COVID – as a framework to analyse the conversations, and deployed text pattern-spotting software and an AI sentiments bot to explore how people’s attitudes changed. As they wrote in their report:

“The sessions […] demonstrated that having the space to come together, reflect and discuss is in itself an act of creating change. The conversations show a gradual strengthening of resolve and decrease in anxiety about the future, possibly through the reassurance of being connected to others in the same situation. The shift towards “Winning Ugly” [the most positive of the four Long Crisis scenarios] suggests that this process of self-identifying and locating oneself within a bigger picture may help a coming-together, a ‘larger us’ mindset. It envisages a new kind of state which acts as a platform for ‘enabling, connecting, collaborating, and catalysing’ a power network shared between communities, organisations and government.”

This was a group of people arriving at a greater sense of agency, and indeed a desire to act, through a process of collectively exploring futures.

Why is this important?

Current systems – political, economic, social, ecological – are not working. The pandemic is a bitter taste of things to come if the climate and nature crisis intensifies, society continues to polarise and atomise and inequality widens.

Communities will come under even greater pressure. Many will be marginalised and forgotten, with terrible repercussions for livelihoods, health and wellbeing. But creating thriving, resilient, powerful communities could be the starting point for a reconfiguration of the way things work. An economy driven by locally-owned and locally-run enterprises rather than wealth-concentrating international banks and big business, and a politics rooted in community participation and radically decentralised decision making, rather than over-centralised policymaking. Such a system, rich with the local social infrastructure that underpins relationships, connections and trust, would have a better chance of creating the conditions for people to lead fulfilling lives, and regenerating the natural world.

People in communities having the opportunity to ‘future’ is a critical part of achieving this vision.

I agree with Stuart Candy when he writes that futuring is a right, not a luxury. Even though the future is just a conceptual space, if we allow it to be dominated by those in positions of power now, those power imbalances will persist. We can’t create a more equitable system through an inequitable process.

So, something like ‘community-led futuring’ is a kind of radical act. But there are urgent and immediate priorities like crime, hunger, loneliness and mental ill-health to deal with – the ‘frontline’ issues that demand urgent and immediate work. People active in their communities working with these challenges are usually incredibly busy, under huge pressure, and often poorly paid, or not paid at all, for the work they are doing. It is vanishingly rare for them to be invited into, or to have the headspace to host, conversations about the future. But not having the time and opportunity to participate in exploring the future is another form of exclusion. We need to work harder to create the space for these important conversations.

At Local Trust whenever we have invited people involved in the Big Local programme to do some futuring, people have jumped at the opportunity and really felt the benefits, even just of sessions lasting one or two hours. One of the communities involved in the programme did a brilliant piece of work – though they didn’t call it ‘futuring’ – engaging around 400 young people in the community aged from 4 to 20 to explore the challenges their part of Hackney in London faced and what sort of changes they wanted to see. When the opportunity is there, people will take it.

It doesn’t have to be difficult. Nesta’s recent research exploring ‘Participatory Futures’ gives loads of examples of community futuring and practical suggestions for how to do it. A simply structured conversation can unlock a lot. The ‘futures conversations‘ toolkit that we used in the Civil Society Futures Inquiry provided a straightforward set of questions and a structure for how to hold a futures session, and sixty different groups across England took up the opportunity, making a significant contribution to the findings of the Inquiry. The recent Emerging Futures Fund from the UK’s National Lottery Community Fund, which gave £2m to 51 grantees to “try and build futures literacy and foresight capacity in local communities across the UK” is incredibly welcome, particularly during a time of crisis, and I hope a sign of things to come.

Futures can help people think differently about the world, adopt more agency and become more powerful. If we can create spaces for communities to do this, the results could be transformational.

Great read. I particularly agree that not having the time and opportunity to participate in exploring the future is another form of exclusion. Also, any futures exercise benefits from having diverse perspectives in the room. The more diverse we are, the greater the range of possible futures we can imagine together.

[…] Via The FutureCenter. […]