The signs of climate emergency are increasingly around us as lived reality, but a strange disconnect still prevails when it comes to current policy and action. Iain Watt calls out the dissonance between future pledges and present-day actions – and the crisis of imagination underlying our predicament.

Spare a thought for the citizens of Lytton, British Columbia. “Out of the frying pan and into the fire” is meant to be an idiom, not a lived experience – yet, after breaking records by reaching a temperatures close to 50C early this week, the community has now been devastated by fire.

Those temperatures are utterly unprecedented. Yet the harrowing videos of citizens fleeing as flames dance around their vehicles aren’t. In fact they’re ominously reminiscent of those from California and Australia in recent years.

Indeed, as traumatic as the impacts on Lytton – and Paradise, and Mallacoota, and so many other communities – have been, there’s more to come. We’re just entering the age of climate disruption, and these are just the opening salvos of the climate battles that lie ahead; mere foothills before the Himalayan impacts to come.

Some scene-setting:

- The planet is now 1.2°C warmer than it was in pre-industrial times.

- And given that the carbon budget for 1.5°C (which itself doesn’t guarantee staying under 1.5°C, but simply gives a half-decent chance) is expiring quickly, whilst global emissions are not yet on a downward trajectory, our chances of remaining under 1.5°C now look vanishingly slim.

- The impacts we’re seeing at 1.2°C are traumatic enough, but projected impacts at 1.5°C are terrifying. To pick just one example, we are projected to lose 70-90% of tropical coral reefs at that point – and bear in mind that some 500 million people have “a high degree of dependency on ecosystem goods and services provided by coral reefs.”

- Yet those projections don’t factor in the possibility of crossing a critical ‘tipping point’ that could shake up global climate significantly. The odds of such a ‘flip’ increase the warmer the planet gets, and there are already some worrying signs from different parts of the earth-atmosphere system…

This last point adds an ‘unpredictability’ joker into our ability to plan for the future. Not only will we have to adapt to the changes that we know are coming (rising sea-levels; warmer-sea-fuelled hurricanes; stronger and longer heatwaves), but we’ll also have to deal with surprises and shocks.

We tell ourselves – and hope desperately – that even a climate-changed future will be predictable. That the grain belts will simply move north; that we’ll be able to grow wine across the UK. But these hopes assume a linear, reliable transition to a ‘new normal.’ Maybe that’s what we’ll get if we’re very lucky. Although, even then, the impacts will be severe – research recently published by Forum and Acclimatise, for example, finds that, under a high emissions scenario, half of global cotton growing regions will face ‘drastic changes’ by 2040 (as a result of high or very high exposure to at least one of the climate hazards considered in the research).

But the warmer we let things get, the greater the chance that we experience climatic shifts rather than simply ‘deviations around the norm’. What if we get churn, rather than linearity? If future climate jumps from turnip weather one year to grape weather the next, we don’t get turnips and grapes, we get failed harvests…

Civilisation has emerged and thrived within a period of climatic stability that – in geological terms – is quite unusual. Even the regional climatic swings that have been used to downplay the risks of climate change (Little Ice Ages; Medieval Warm Periods; and the like) are small blips in an overall period of reliability. Perhaps we take such stability for granted? And that prevents us from even imagining that climate could be distinctly different?

Our glorious little planet has always had its inhospitable parts. But, in our collective wisdom we’ve avoided living in those places. Yet, not too far from our deserts we find temperate- and Mediterranean-type climates where we live in our millions. And we’re now nudging those previously hospitable regions towards the inhospitable (and, at worst, unliveable). Late June saw the Pakistani city of Jacobabad – with a population of some 200,000 – reach a ‘wet bulb temperature’ beyond that which the human body can handle. And Jacobabad is but one of many towns and cities located in the Indus Valley.

As those, and other, places become increasingly hazardous, people will move. And as sea level rise continues to bite, coastal populations will start to move too (albeit perhaps after a series of “paralyzing battles over the why, who, when and how”). And, from Syria through the Mediterranean to Central America, recent history tells us that, when people start to move, there are difficult political implications.

We’ve recognised the coming disruption to some degree – there’s no shortage of declarations that we’re in a climate emergency, for starters. Yet the climate emergency is a curious beast. To paraphrase Inigo Montaya, while we keep using those words, we don’t seem to understand what they mean…

- It’s an emergency. But while we “recognise that coal power generation is the single biggest cause of greenhouse gas emissions,” it’s still not quite the time to stop burning it. And it’s certainly not the time to stop looking for new oil and gas reserves.

- It’s an emergency. Yet it’s still ok to take a quick jaunt on a plane to, erm, talk about that emergency. Or to make the case for a post-Covid ‘green recovery’.

- It’s an emergency. But we’ll continue to build new homes in flood plains. And, indeed, slack off on adaptation full stop…

That’s not to say there isn’t a lot going on. Alongside this ‘how-the-hell-is-this-stuff-still-happening’ list, I could have offered up multiple ‘reasons to be cheerful’ (perhaps with Big Oil’s day of shareholder pain front and centre).

But given the magnitude and urgency of the climate emergency our collective response remains woefully insufficient. It offers incremental change through established systems, when we need emergency measures!

Our fixation on 2050 is clearly part of the problem, not because net zero by 2050 isn’t an appropriate end-state to aim for, but because – for it to be a viable end state – it only works if there is radical, and sustained, change over the next decade. The climate modellers know this. But the world at large clearly looks at the 2050 goal and thinks, “we’ve got until 2045 before we *really* need to act, yeah?”

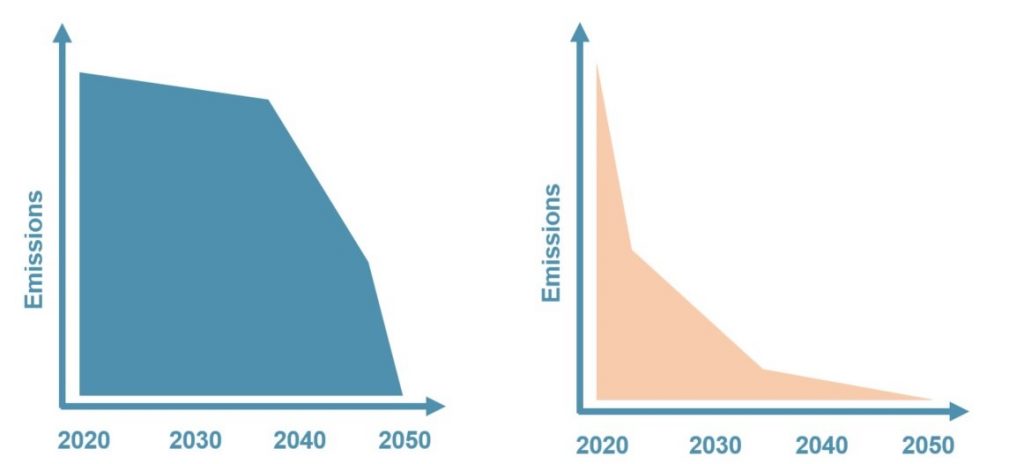

Leaders perhaps need a reminder of some basic “area under the curve” maths. Unless we reduce emissions immediately, the remaining carbon budget will be used up well before 2050:

The total emissions (the area under the curve) in a net-zero-by-2050 ‘pathway’ like that on the left are considerably greater than those on the right (which more accurately reflect the carbon budget), and with our remaining carbon budget so tight to begin with, would represent a budget-buster.

Yet getting ourselves on a pathway that even gets close to resembling the ‘necessary’ pathway on the right involves radical change, from now. Change that, for the time being, remains a pipe dream.

I also think that, in the collective environmental effort to avoid doom and gloom at all costs (based on the untested and, in my opinion, flawed assumption that those roads lead to despair and inaction) we’ve soft-balled the risks of climate change. In so doing, it shouldn’t really come as a surprise that business and government have largely carried on as normal…

But perhaps we’ve also struggled to even imagine what a rapidly-decarbonising world might look like. As with our inability to imagine a climate radically different from that we have now, we also struggle to imagine a way of living that is radically different from today. As Roy Scranton has put it, we are; “biased toward… a belief that whatever exists is and was and will keep on being.”

The immovable object of the modern economy (and our Western way of living) is, however, now coming up against the unstoppable force of climate change.

It now looks like we’re going to cross 1.5°C, perhaps as soon as the end of the decade, and we’ll therefore have to collectively negotiate the geophysical churn that this will bring to bear. Alternatively, the only way we’ll now avoid crossing 1.5°C (or even give ourselves a chance of 2°C) is through the rapid and complete transformation of the global energy, food, transportation, materials – and likely economic – systems.

To murder Yeats’ classic, the centre cannot hold. Things will fall apart. The ‘centre’ doesn’t yet seem to have realised the predicament it’s in, but it’s hard now to see a future that isn’t characterised by disruptive change. As the ever-eloquent Alex Steffen has argued; “We’re not yet ready for what’s already happened.”

Preparing for known climate impacts would be challenging enough, but we now also have to build sufficient flexibility into our systems that they can cope with ongoing disruptive surprises as well as trends. That’s going to be some dance for all of us to navigate. But there’s not an option for any organisations to sit this out. Climate change is going to fundamentally transform the context within which we all operate, and it’s surely wiser to face this head on, rather than look the other way.

Join discussion