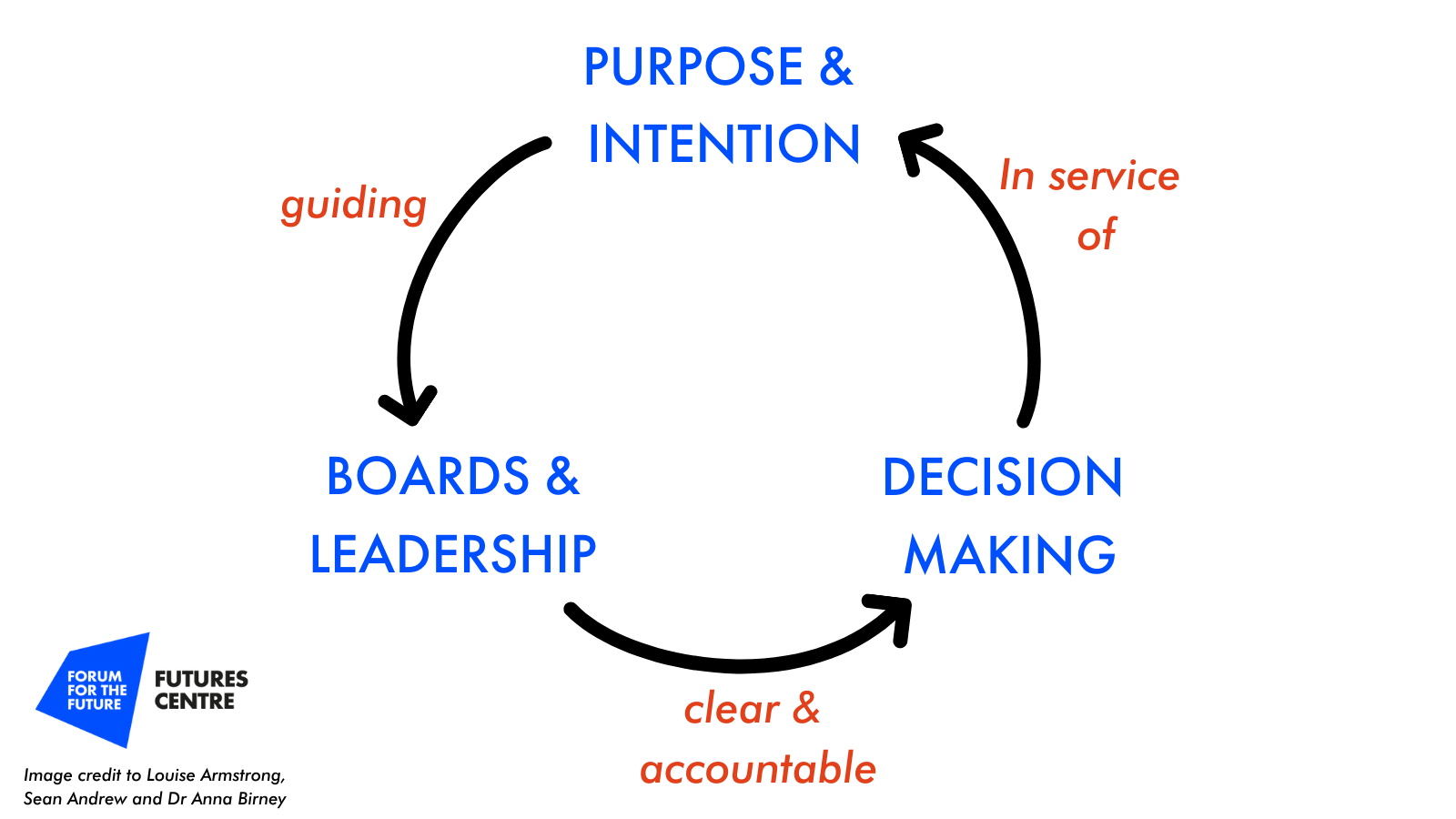

In this final installment of our series on governance, we introduce the “governance flywheel”1 which highlights three fundamental linked areas that if they are deliberately seeded and nurtured, individually and together, can create the momentum needed to cultivate and grow healthy governance systems.

Co-written by Sean Andrew, Louise Armstrong and Anna Birney

*If you’re arriving at this blog fresh, you might want to read our first piece on how we organise for change as it provides some context about our governance inquiry.

Shifting governance

This is a big topic and it can be overwhelming and hard to know where to start. So far in our series, we’ve explored what governance is and some of the myths to be busted and reimagined, and the need for a space to explore this with others. This blog introduces the “governance flywheel” as three intrinsically linked and fundamental areas that if given the opportunity, can create the momentum needed to cultivate and grow healthy governance systems.

These three critical governance elements have been identified from our own experience and through our inquiry over the past few years.

These are areas we have experienced or seen as being both challenging and also as potential opportunities to unlock different ways of coming together. If intentionally designed and continuously attended to, they can be grounds for the emergence of healthier forms of governance.

When not tended to – these areas can keep us stuck, sucking up time and energy, creating resentment and conflict, and result in relationship management (versus building) and politicking. When done well they can transform how people experience themselves at work and how they show up, their relationships across different levels and functions, and ultimately the potential impact of our organisations.

With care, intention and attention, these domains do not have to be areas we might otherwise wonder about and stumble through. They are both things you can start to explore tomorrow via micro experiments (e.g. how are we going to make a decision at the end of this meeting) as well as areas that can have significant influence on the systems change impact your organisation is working towards (e.g. aligning around a clear and deeply shared intent for our organisations purpose).

Decision-making:

A convergence point for so much of systems change is how we make decisions. The process of decision-making crystalises how we work with our own power, each other, and the resources we have available to us.

At worst, decision-making can be unclear, happening in a black box, be too fast/too slow, and having us going around in circles. Just when we thought a decision had been made, behaviours that counter what was “agreed” to occur or for someone else to come in strongly with another opinion.

“I don’t know how decisions get made – that highlights part of the challenge”

“The scale of decisions that need to be made cannot be held by a select few”

We’ve found that it is important to remember that a decision-making process starts way before a decision is actually made. A healthy decision-making culture involves a process of experimenting with different perspectives and possibilities. It is a connection and momentum-building effort. The key here is remembering that we are not simply “trying to make a decision”. Rather, we are attempting to build a shared and collective understanding of a given situation (including different views) through a process that flows into a proposal and formal decision point down the line

This requires that we do not fall into an unhelpful “yes” or “no” binary too quickly. There is a big difference between a “YES!” and a “uhh sure Okay” or a “NO!” and a “umm ehh not really”. We have to allow space and time for nuance. This is about not reducing complexity and falling into extremes that try to simplify or ignore the space in-between a decision point.

The practice here is learning how to stay in the “groan zone” of deliberation and dialogue (embracing different views, facts and getting into a questioning and idea-generating mode) before prematurely diverging. This is easier said than done as the groan zone can be intolerable for some people as tensions build up and we can easily slip into “let’s just make a decision and move on!” We know this results in unsustainable decisions where peoples’ dissatisfaction will show up in all kinds of covert and even overt resistant ways (remember the resistance line).

We can work with and in the groan zone space by having a shared intention and working in service of our purpose. With intention and purpose, we can increase our tolerance for giving more energy to building understanding and connection via hearing all the different views, particularly the minority views.

Here are a few participatory approaches to help us stay in the groan zone while we experiment with different experiences and views:

The most simple (not necessarily easy!) approach might be playing around with consensus testing methods that help us see the range of different thoughts and feelings people have about a topic. By surfacing these views, we are able to guide our conversation towards a formal decision that is grounded in context. We like to use methods like “sense of the group” (a facilitator articulates emerging options), “straw poll surveys” (sticky dot preference), gradients of agreement (spectrum lines or 5 finger consensus), or soft shoe shuffles (an embodied way to see where people literally stand in a position in regards to an issue). These methods all bring people along versus waiting until the end to hear what people think. So how can we support people to voice their thoughts early on so that the actual decision we’re primed to make considers the whole (shared purpose) and its parts (individual needs/wants)?

When it is actually time to converge and make a decision, it is all about creating clarity and ensuring people are actually ready to go into a decision-making process. We do not want to make a decision due to dialogue fatigue as this will result in an unsustainable way forward.

A golden principle here is to have clear decision-making “rules”. For example, how is the decision going to be made? Who is going to be involved in figuring this decision-making approach up? Who is going to be involved in what decisions? How are the views of those not present being integrated and considered? Who is going to be informed and how around what decision was made and how? And how long do we have to make a decision (having constraints is key here)?

There are a range of different decision-making approaches and protocols that can be explored, and what is important is that we do not fall into one decision-making approach. Every context is different and sometimes we need a swift consent approach while in other situations we need a consensus or advice-based process that includes more consultation.

- Taking a decision to end the Boundless Roots project

The process of making that decision involved really listening to the needs of the community and those involved, being honest about the commitment and energy from those stewarding the work in the past or who might in the future, and also engaging the senior management team of the host organisation (Forum for the Future). Traditionally it might be the host organization that decides on this type of decisions, but it was important for the spirit and ethos of the work and vital for the success of this community-centered project that that decision making was expanded and transferred to the stewarding group.

In the end, despite there being lots of energy and a need for this project and community to continue, the stewarding group decided that it should end after the initial 2 year period.

Practical things you can do to improve your decision making:

- Map out the different types of decisions that you make, when they happen and who is accountable

- Be explicit about who and how decisions are made

- Be clear about how/when a decision has been made and communicate to all involved (particularly those most being impacted by the decision)

- Practice and experiment with different decision making methods as see what works for you and your group or organisation (e.g. a great resource from The Hum on

“4 Decision-Making Methods for Decentralised Teams” that we’ve taken inspiration from).

Purpose and intention

We often treat governance as static and not something that evolves over time and this goes for your purpose as well. Without clearly defined purpose and intentions you’re at risk of reacting because that’s what’s come before, rather than really asking what is happening now, changing, what is needed and what purpose can your group organise around.

Intentions are useful as they make ambitions and dreams tangible and allow more agency to act rather than be overwhelmed by far-off targets. This is about creating a shared intention. This is without trying to get so detailed with your intention that you are unable to get into the process of doing and learning.

While it can feel frustrating and uncomfortable to stop and reflect, it can bring up tensions and misalignment that are otherwise easily overlooked. It is vital to reassess and look honestly at what is and to refine and hone your purpose and intentions on a regular basis.

- Evolving Forum for the Future’s educational offerings

“School of Systems Change: Growing a global community of change agents is our best chance to accelerate a transition to a sustainable future.”

When developing the School of Systems Change, it started with a process of collecting market insights, understanding what the world needed, the organisational history and the founding story of why Forum had embarked on education programs initially. What has become the School was an evolution of the Masters program so it is key to root back.

In addition to this, what was really important and can often be overlooked, was the purpose of individuals committing to leading this work. Allowing for this comes through a deep reflective process and space for personal honesty about what is driving and motiving us. So the School’s DNA and essence came from a combination of people’s purpose committing to this next endeavour in the context of and meeting needs in the world.

Practical things you can do to improve your purpose and intention setting:

- Think about your purpose and how it’s changed over time, what allowed that to happen?

- Work with enabling constraints (principles and heuristics) which serve as little guidelines that help us make decisions and stay coherent to the shared purpose. People might have various expressions and experiments that serve this purpose. Embrace these as enabling constraints that support progress rather than telling people exactly what they have to do

- How will you know when you’ve [achieved] your intentions? Notice when it might be time to stop, shift or evolve. Retrospectives grounded in honest sharing and feedback about both objectives and relationships are key here

- Practice refining your purpose and intentions for smaller decisions or pieces of work – before tackling the larger ‘organization’ or movement purpose and intentions

Leadership and Boards:

Boards and leadership teams are often the first things organisations address when they think of governance. People in these groups and positions traditionally wield a lot of power, feel a deep sense of responsibility, and impact both what is possible and what people feel able and legitimized to do and not do. They can be the site of unhealthy power dynamics, stress, heartache, and emotional labour.

A common dynamic can occur when boards are disconnected from the organisation it is there to support and serve – and the formality of the legal responsibilities outweigh the approach and impact being sought (see the innovative idea of “shadow boards” here).

But at best leadership teams and boards can create an enabling environment for groups of people to work together and create impact. Be part of really listening, understanding, and making sense of what is changing and create a vision and direction of travel to guide people and actions. Providing a strategic view of what’s needed, getting out of the way when required, and stepping in when required. Enabling individuals and groups to unleash their potential and feel supported to bring what they wish.

- Forgiveness project

Some years ago the board was having a difficult time deciding on the leadership for the organisation beyond the Founding director. There have been a series of failed recruitment processes and a sense that the relationship between the staff and the board and the desired culture wasn’t working as well as it could. They’d reached a crunch point.

Part of the work of the Forgiveness Project is people listening to each other and being in the circle, so the board and the staff decided to practice this too. There was a long session with the board and staff sitting on the floor together and listening to each other; taking time to hear the frustration and anger of the staff and reflecting on the practice and behaviour of the board. It was a moment for the board to ask and reset what the nature of board leadership is required. It looked at how the board was there to serve the staff’s needs and the organisational purpose and not to imprint their own ideas and vision. This shifted the practice of the board to be an enabling force of the organisation. This philosophy has been shared when recruiting new board members. It’s served the organisation well as the pandemic hit and allowed for inclusive and respectful decisions to be made around finances and staffing thus allowing a new way for the organisation to thrive.

Practical things you can do to create an enabling board or leadership environment:

- Define the purpose of your board and who they are accountable to – does that match the ambition and intention of the work you’re trying to do?

- Bring a level of honesty and humanity to the conversation, allowing people to bring their full selves into the conversations, not just the professional or positional identities

- Create the space and time to understand and listen

- Appoint a chair with facilitation and listening skills

- Build in communication channels and feedback loops between different people making up your group or organisation

- Create an enabling environment for all to play a part in leadership

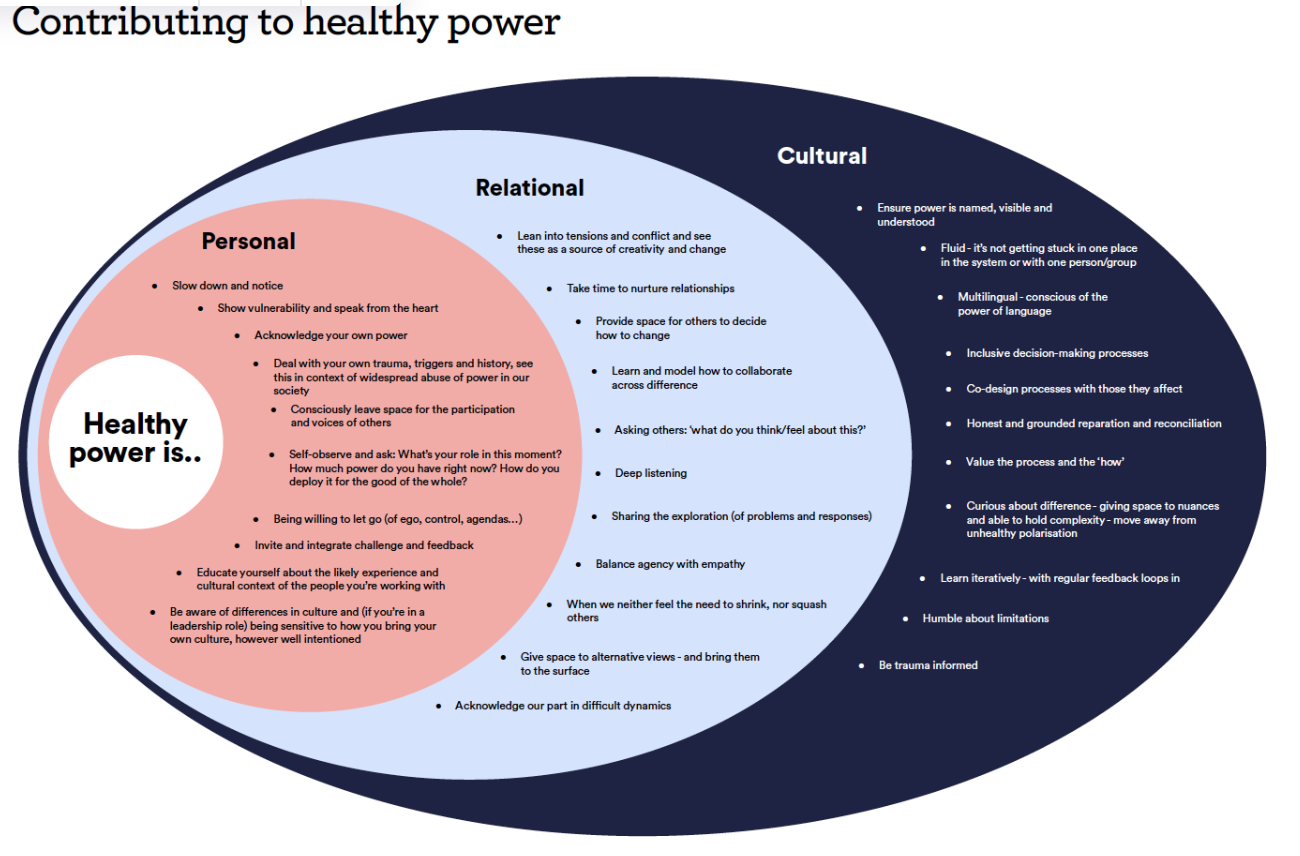

Healthy Power: a necessary condition for systemic governance

The thing that connects all of the other three elements is power in how it is framed and yielded. Regardless of whether you see it and work with it now – it is flowing everywhere.

Power is “the ability to galvanize energy, influence actors, and mobilise resources to achieve desired goals”.2 Power also weaves through all our system structures, relationships, and the ways we think and behave in the world. So we cannot write about organising for change, decision making, purpose, and intention, or leadership and boards without bringing in a power lens.

So how does power relate to governance?

Governance relates to the structures and the process of how we organise and ultimately get stuff done. It is therefore about the relationships between the people who are deciding, what their purpose and intentions are, where they sit (their rank) in relation to each other, and how they understand and use their own leadership, this is not just affected by positional formal power but also by sociocultural, spiritual, historical, informal powers. Much of governance is also undertaken by those with positional power, either as elected or appointed. How they wield that power and understand it is extremely important. Much of power is used in ways that are unhealthy that is using these positions to maintain power over others. Healthy forms of power are ones that use positional power to enable, empower others, and distribute decisions closer to where the knowledge of the impact is.

In any system with humans in it, power relations exist, whether you formalize them or not. Healthy governance has the potential to support healthy power, it can provide the structures to support relationships and work better together.

Jo Freeman’s reminds us in her essay the Tyranny of Structurelessness that “without formal structures, informality rules” and that ultimately “structurelessness in groups does not exist”. If you refuse to define power structures, informal ones will emerge almost instantly. So power relationships, personal power, and how they operate together is essential to name, talk about and continually work with so that it does not create unintended harm or mistreatment for both the people you lead as well as the purposes you are serving.

“Whenever nobody is talking about power, it almost unquestionably exists, at once secure and great in its unquestionability. Whenever power is the subject of discussion, that is the start of its decline” – Ulrich Beck

- An everyday practice of check ins

One way of actively working with power is about people, and in particular leaders, acknowledging their power and perspective and creating spaces to openly listen to other perspectives with an openness to shift your own.

A micro practice of this is hosting ‘check-ins’ at the start of meetings, which is particularly important when decisions are being made. Checks in invite everyone to speak at the start of a meeting – to feel valued and listened to – to share how people are, the context for how they’re arriving, and inviting a place to express and share concerns and perspectives early on which might impact the direction of the conversation and how best to use the time and space together. It requires those leading a meeting to lean in and lean out, which allows the sharing our your perspective honestly while making space for others to share their perspectives and opinions. It takes practice and over time this can create greater trust, particularly when it’s clear others the perspectives and views of others are important and needed in decision making or if these views are not take on being clear on why.

Practical things you can do to be more power informed:

As we wrap up this mini-series on systemic governance, our hope is that we’ve been able to share a little bit about our experience of how governance manifests in our everyday organisational lives. Ultimately it is an invitation to pay attention to not only the structural shifts we need but also the ways we show up and relate to one another in our work. We’d love governance to be something we don’t leave to the end of our organising efforts, but rather through our everyday practice of gathering and wading through change together, and a vehicle for systems change in itself.

Please join the dialogue and let us know what has or has not resonated for you through this series so we can continue together to work with governance in a way that brings us connection and creativity.

If you’d like to chat more, get in touch at s.andrew@forumforthefuture.org

Explore the series

Part 1: Governance – the overlooked route to transformation: How can we best organise for change?

Part 2: Exploring transformational governance together

Part 3: Reimagining governance myths

1 Flywheels are rotating devices to store kinetic energy. They capture the momentum in a rotating mass and release the energy by applying torque to a load. The potter’s wheel is often cited as the earliest use of a flywheel.

2 Musho Hamilton, Diane. Compassionate Conversations (pp. 102-103). Shambhala.

Join discussion