As part of this year’s Future of Sustainability, we partnered with Next Generation Foresight Practitioners (NGFP) and the School of International Futures to explore emerging models of value creation, new approaches to risk management, and how businesses were embedding plural forms of knowledge to inform pathways of resilience. As one of the largest global networks of young futures, the NGFP network allowed us to draw from the practice of younger practitioners, especially from the Global South. Mansi Parikh, a 2020 NGFP fellow joins us to explore more contextually led business models for resiliency, drawing on her experiences and insights from India.

Mansi Parikh is an award-winning Foresight Strategist and founder of Future Tense Inc. A consummate generalist she explores the liminal spaces between the past, present, and future, real and imagined. Through experimentation and research, she uncovers new perspectives & deconstructs the mundane to imagine possible tomorrows. A full-stack venture builder she works with businesses to help create new business models through scenario planning and business design. She has worked on strategic foresight, business design, innovation, and brand strategy projects for brands like Playboy, Danone, Domestic + General, Ontex, Bacardi, Scotch Malt Whisky Society and building social impact models for regenerative rural futures for marginalised communities at Balipara Foundation.

My formal education includes an undergraduate degree in engineering followed by postgraduate education in business, which meant years of reinforcement in techno-solutionism and current capitalist structures. Despite this, an intuition began to take hold that there was something amiss in this mainstream narrative of how the world is supposed to work, that maybe there is a different way to think about how we live, work, and build things. Over the years, through experiences working with grassroots communities in the Eastern Himalayas, witnessing the growth and challenges of India as a nation, and working in foresight, my intuition has proved true in myriad ways.

In my ongoing journey of unlearning certain patterns of thinking and re-orienting my mental models for imagining more thriving and vibrant futures, I happened to pick up Arati Kumar-Rao’s Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink. The book is a beautiful, heart-wrenching chronicle of the most threatened Indian ecosystems, it paints a vivid picture of the struggles between tradition and modernity playing out in the most extreme ways. No passage in the book captures these extremes quite like this one:

“As we crisscross Jaisalmer district, we continuously encounter two different worlds. In one lived a people grounded, observant, wise to the magic and limitations of the desert, and therefore able to survive, even thrive, in a seemingly hostile environment. In the other lives officialdom – a hodgepodge of ‘departments’ and ‘bureaus’, unaware of the intricacies of the land, intent on imposing their will on an ecosystem they continue to misunderstand.”

Arati Kumar-Rao’s Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink

It really reinforces how somewhere along the way instead of using our modern understanding of the world and building on our existing knowledge systems we polarised them into two extremes – “traditional knowledge” the rich wisdom gathered over generations through experience and passed down in the forms of culture, rituals, and stories which have somehow evolved to mean an “un-scientific” antithesis of “modern technology/science” developed through carefully designed experiments and meticulous gathering of data. Somewhere along the way, we’ve added the word “quantitative” as a silent qualifier to the data gathered putting traditional knowledge systems, which are largely informal, and modern science/technology at the opposing ends of an ever-widening spectrum.

Given the scale of challenges we face with the threats brought on by climate change, conflict, and stagnating socio-economic growth, we need to bridge this gap to develop more resilient futures; we can start by redefining “scale”, “value” and “growth” for flourishing futures. Can we envision futures where we move beyond techno-solutionism to blend the promises of modern scientific knowledge with the wealth of traditional knowledge in a way that might unearth more complex but far more adaptable ways of being?

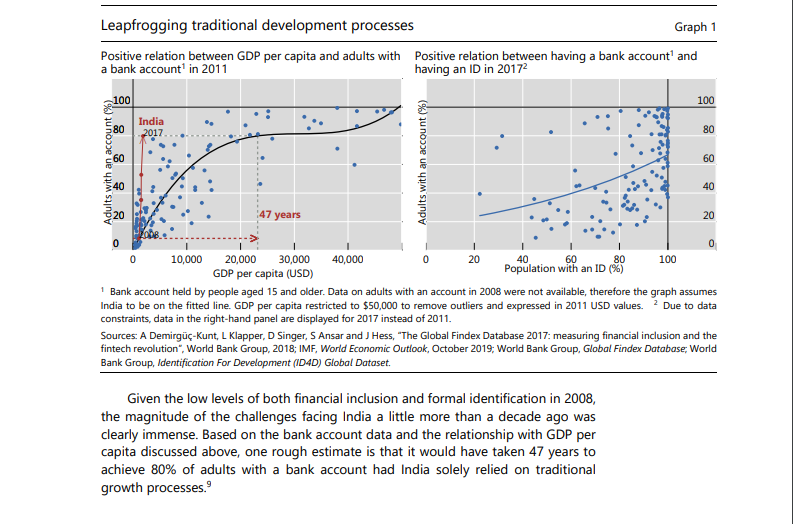

Looking closely at where growth and innovation are currently coming from in developing nations, much of the success has come not by aping the models that succeeded for their Western counterparts; instead, it has come when they redefined “growth” for themselves, to leapfrog their western counterparts.

Digital Public Goods

For decades, the Silicon Valley model was considered the standard for technology development and innovation i.e. technology funded by private money and built by private entities since they are considered more ‘agile’. But what if we question this assumption that private entities are better equipped to build technologies for massive global populations and start exploring technologies designed on cultural cues and built as public goods? It’s not as far-fetched an idea as you might think. India built and launched the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in 2016 and subsequently in 2020, Brazil launched Pix to facilitate instant peer-to-peer and peer-to-merchant payments addressing financial access gaps. Before these mechanisms, large pockets of the populations living in remote parts of these nations who did not have access to physical bank branches were largely excluded from the formal financial system. In a move to improve access, the Central Bank for both countries sought to build more open banking and payments systems and both systems have been built as public goods with public money.

Source: The design of digital financial infrastructure: lessons from India, BIS Paper

On the surface, UPI is an interface layer between people and their money in the bank that can be integrated by all payment providers to facilitate instant payment transfers, either by scanning a QR code or using an email ID style UPI ID (eg. xyz@bankname) which is linked to their bank account. It is already being expanded to allow asynchronous small transactions in low network areas as well as creating a version of UPI for feature phones that can work via Interactive Voice Response (IVR). The government is also currently trialing multi-currency international payments and UPI ATM withdrawals and is successfully working with countries like Singapore and UAE to integrate UPI into their financial systems to enable remittances to India.

Delving a bit deeper into the UPI structure reveals an interesting new phenomenon of Digital Public Goods (DPG). India’s UPI is built on an even more ambitious India Stack, a digital interface stack (i.e. a set of digital technologies that are constructed to be flexible and interoperable enabling public and private stakeholders to build a variety of solutions and services) that enables Digital Identity i.e. Aadhar, Payments i.e. UPI, etc., Sensitive Data Management i.e. DigiLocker, etc and is currently in the process of testing and rolling out Open Networks:

- Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) – interface layer that enables a more open marketplace system to enable e-commerce in the country for businesses of all scales seeking to break the punishing walled gardens of platforms like Amazon, Uber, Swiggy, Flipkart, etc. in favour of a level playing field for customers and for new players seeking to enter the markets at any scale.

- Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN) – This is an attempt to build an open network that digitises the processes of originating, underwriting, and servicing a loan along a set of common standards, through a single platform to democratise credit access to small businesses and vendors.

While the technology and the proposed solutions are certainly exciting and are already showing some signs of improving financial access and inclusion in both India and Brazil, the key feature of designing for financial resiliency has been the building of interventions with cultural and regional nuances in mind. But are these isolated signals of context-specific design for financial access and enabling growth or have we missed similar signs of other models of development in the past that challenge the mainstream norm of profit for a few?

Looking Beyond Capitalism

As we confront wicked problems (i.e. complex issues with numerous interdependencies that are impossible to untangle or isolate) pure capitalism is increasingly being challenged and discarded in search of more anti-fragile models which discard the primacy of the shareholders to build more equitable models that prioritise a balance between various human stakeholders, society and nature. Patagonia recently announced a unique ownership structure and a few years ago Chobani gave away ownership shares to its employees worth 10% of the total company value.

Co-operation

A model that has found much success in India is the Co-operative model (aka co-op), also receiving a push from the current government policy machinery. Amul is India’s largest and most famous dairy co-op set up immediately post-independence. Its early success inspired the adoption of the co-op model to form several smaller dairy collectives across the country and has subsequently spurred India to become the world’s largest dairy producer, of which Amul alone has a turnover of ~USD 8.5 billion.

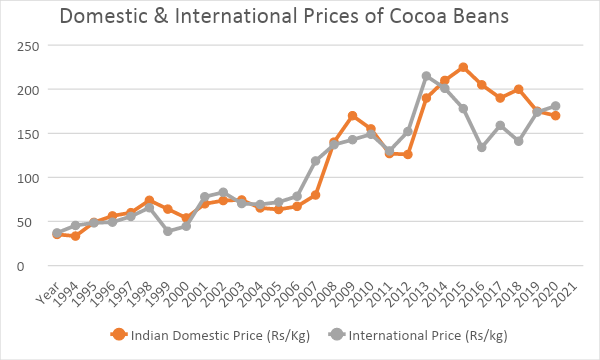

Apart from spurring economic growth for all its members, co-ops have also shown great resilience to larger economic shocks. India’s CAMPCO (Central Arecanut & Cocoa Marketing and Processing Co-operative Limited) with a turnover of ~USD 240m has been able to command cacao prices above the international average and managed to escape the price crashes from 2016-2019 due to its co-op structure, which prioritise the benefit to the entire collective instead of the largest/most powerful producers.

Source: www.dccd.gov.in; Directorate of Cashewnut and Cocoa Development, Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, Government of India. Table in Annexure 1. (Alt source)

Co-operation for Regeneration

Through my previous work at the Balipara Foundation, I studied and helped design co-operative models to manage natural resources. I was involved in the team establishing and funding a community forest initiative in the Eastern Himalayas as a method of mitigating human-elephant conflict and improving social mobility in the indigenous communities. This project has demonstrated great success over the years and has recently grown into a greater ambition of rewilding 1 million hectares in the Eastern Himalayas through the Great People’s Forest initiative. Studies from different parts of the world show that community-managed forests have lower levels of degradation and deforestation, and greater capacity for carbon storage. Not only are the forests thriving but they are also yielding better livelihood opportunities for the local communities. The success of these community ownership models points to the possibilities that might emerge when combining the traditional wisdom of the indigenous communities who understand and respect the complexity of the ecosystems with more modern commercialisation and scientific structures which allow for the communities to sustainably benefit from these ecosystems.

Evidence seems to point to the efficacy of building public and private interventions suited to local geographies and cultures to leapfrog current systems in the face of climate impacts and economic shocks.

How then do we extend and encourage this kind of innovation across the public and private sectors? Can we leverage the intuitive knowledge of the nomadic desert-dwelling tribes who have walked the deserts and can intuitively glean the gradients of the land to know where to dig for water, with policymakers, government bureaucrats, or planners/architects redefining how we innovate and change?

Can we revive and modernise the ancient step wells in India and what can we learn from the original architects who created a masterpiece of both engineering and behavioural design?

Apart from accommodating the varying water levels through the seasons with the steps leading down to the bottom, step-wells like Rani ki Vav UNESCO World Heritage that has intricate cultural and religious carvings at the centre to discourage washing of clothes, livestock, or defecation thereby preventing water contamination.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Maybe, in developing nations as we seek to build resilient systems we redefine “scale” and maybe think small instead of thinking big? After all, 30% of India’s GDP contribution comes from MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises). Kirana stores (i.e. Mom and Pop corner shops) make up 90% of India’s retail market and seem to have their finger on the pulse of the customers in their catchment, no algorithms, they probably pioneered the use of WhatsApp as an ordering platform well before WhatsApp realised it was a use case (source: my mother has been ordering groceries via WhatsApp for least 6 years). Small businesses in India are usually quick to adopt technology and often find ways to make it work for them. Imagine if we were to build “small” technology really tailored to their needs… could we supercharge their success? Therefore, adding more wealth to hyperlocal economies rather than a few large players?

Smart, low-cost innovation has enabled great success in multiple sectors not the least of which is the Indian Space program; the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) launched a successful Mars rover (Mangalyaan) and a Moon Lander (Chandrayaan-3) at a cost less than it takes Hollywood to fake space exploration. Can we blend our scientific rigour and ingenuity with our traditional, cultural knowledge to redefine success for ourselves? Maybe our shift in mindsets and design approaches will inspire nations like Spain to work with their local communities to design systems that revive and adapt ancient water management systems like acequias instead of shipping water in tankers to combat drought.

Every day we are confronted with statistics like 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2050 and headlines like AI will replace millions of jobs. Rather than orienting ourselves such that these futures are inevitable, we should learn to question it more, and delve a little deeper to find out whether resilience may lie in developing rural areas to reduce urban migration or if AI might be more effective in making some human jobs less dangerous or more efficient in conjunction with human intelligence.

When we do ask these questions, it won’t be uncommon to be labeled ‘anti-development’ or ‘anti-tech’, but we need to hold our ground and imagine futures that aren’t based on false binaries. We need to believe that different, more inclusive, and regenerative worlds are possible, what is more, we are already seeing glimpses of them.

This insight was produced in partnership with The Next Generation Foresight Practitioners. Launched in 2018 by the School of International Futures, the network of almost 600 people from all over the world who are using futures and foresight to create positive impact and systemic transformation globally.

Learn more about the network

With immense disruption all around us, four possible futures are emerging. Keeping these four futures in mind, there is a growing call for businesses to focus on five key shifts in order to transform their purpose.

Explore all this and more in Forum for the Future’s new report,

‘The Future of Sustainability: Courage to Transform’.

Join discussion