A city is far more than a collection of buildings and infrastructure: it is alive. A healthy city is in a continual state of renewal: not necessarily expanding but growing new skins, shedding old ones, while maintaining a strong cultural core in its history and traditions. Like all organisms, the health of a city depends on a variety of factors. It needs to be nourished with air, food and water. It needs to flowing arteries to distribute these nutrients to its many cells. It needs space and time to rest and replenish its resources. It needs to rid itself of parasites, and protect its assets from leaks and plunders.

If we want to make our cities healthy, we must embrace all these complex contributing factors. This is why a recent three-day design lab run by UNDP’s City Experiment Fund in Chisinau, Moldova, began with a full day of unpacking the complexity within specific problems encountered in five Eastern European cities: Chisinau, Kragujevac, Nis, Skopje and Yerevan. Multi-sector and multi-generational teams, bringing together government officials, private sector leaders and other citizen activists and young influencers, came to develop portfolios of experiments that would act in synergy with each other to achieve not just short-term remedies but systemic transformation.

We began with team exercises to investigate what lies beneath the superficial challenges they observed.

Take the challenge of air pollution in Skopje. People living there both smell and see it, and also suffer from it. Health is deteriorating, and hitting the poorest the hardest – those with the least capacity to dodge the worst areas or pay for commercial air purifiers. The team from Skopje identified some political and infrastructural challenges underlying the bad smell: corruption in government and frequent changes of leadership, contributing to the absence of any long-term vision for improving air quality; lack of investment in any low-carbon infrastructure, from bike lanes to low-emissions public transport; another thick layer of haze obscuring accountability for any improvements and structures for urban planning and development. Then they delved even deeper, into the mindsets and belief systems that maintain such a high level of inaction in the face of such a clear need for change. “It’s not my problem to deal with” is one common perception, rife not only among those in power, but seeping through to all citizens and businesses. More insipid even than this was the belief: “Even if it were my problem, there’s nothing I can really do about it.” And this belief had bred a deep-seated sense of abandonment, apathy, even resistance to change. Skopje, the team admitted, was sulking! Its attitude was no better than: “Why should I?!”

Good question: Why should a city’s many different actors come together to solve a problem like air pollution? For one, because they are the ones suffering from it. Taking action is no charitable deed, it’s looking after one’s own back in the most basic way. Two, because no single actor – not even the most powerful – can solve such a complex challenge alone. It needs to be tackled from many different angles: infrastructure, technology, legislation, behaviour, finance, digital solutions and more. And three, because there are rewards to reap: public health improvements, productivity gains, improved mental health, community cohesion, opportunities for innovation, and so on.

So how can a city with such a fundamentally disempowered mindset turn it around? This was the central question our team embraced: how might we empower citizens to take action on air pollution? They started right at the root of the matter, the founding narrative, and flipped it around: “My actions matter. I can change things. We will hold government and industry accountable.” They, therefore, planned a series of experiments around community ownership, harnessing tools such as real-time air pollution monitoring to create an evidence base for action, and exploring participatory budget-ing – inspired by Consul in Madrid – as a means to democratize decision-making and infuse it with transparency and accountability.

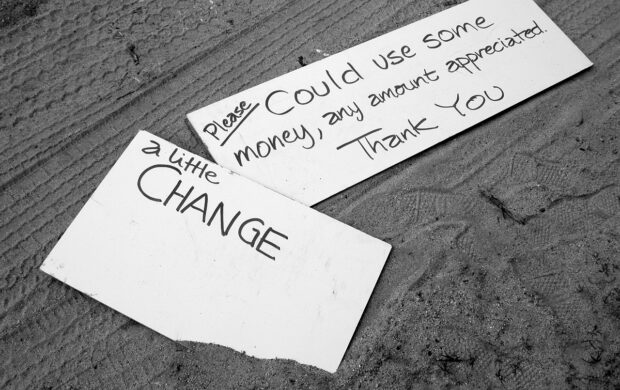

Another city, Yerevan, took on neglect of public spaces – with broken sidewalks, poor lighting and abandoned, untended parks. Their analysis found a stark contrast between the freedoms that money could buy to develop in any and every direction, and the dearth of investment in the ‘commons’: the spaces and resources shared by all. The prevalent belief here was that profit matters more than social development. The team concluded that the founding narrative needed to shift from ‘Me’ to ‘We’. They would design a series of experiments to develop a sense of collective interdependence and responsibility – which would enable people living in Yerevan to develop stronger emotional connections to the spaces they shared, bringing their families into parks, planting trees, developing public art projects. They took inspiration from the artist Al-ice Sharp, whose work makes visible the subtle connections between our choices and behaviors, the systems that influence us, and our health.

A team from Chisinau, the city hosting our design lab, set out to tackle the negative impacts of congestion. Not only do people waste time sitting in traffic, but they are less productive at work, less carefree and engaged at home, more anxious generally – and facing a rise in respiratory problems to boot. In exploring the complex reasons why people end up spending hours every day in traffic, they recognized that behavioural patterns are key. Why is there a rush hour in the first place? Because employers demand everyone begins and ends their day at the same time. Why, they asked – given proliferating resources for more flexible working? The team realized that the city’s centralized urban design has seeped through into people’s assumptions about what matters: the decisions that matter take place in the centre. Being part of those important decisions – being important – means having wheels to take you into the centre. Having a car – and parking that car wherever you like – is the fundamental indicator of your power in the city.

The Chisinau team looked to shift this narrative from ‘The city’s where it’s at’, to ‘I can make changes right here in my community. I have all I need right here.’ The recognized that if they could empower the edges and hidden pockets of the city – for instance, by putting structures in place for decentralization, from high-speed internet and lower bureaucracy to a shift in employers’ mindset – they would unleash a much wider transformation, with benefits for mental health, communities and creativity.

—-

So much for insights into today’s problems. What happens when we add the complexities of tomorrow? This was the theme of the second day of our design lab. Drawing on signals of change from the Futures Centre, and the trends we see emerging around us today, we explored how they could come together to give rise to futures very different from the contexts we may think we understand. With converging trends come more challenges – and also opportunities.

The teams started with exploring one single change they see today – asking what new possibilities it could lead to.

For instance, Skopje took the example of a renewable energy cooperative in Barcelona: how might such as approach to energy generation transform communities entrenched in the tradition of burning wood fuel, gathered by men and consumed by women? What if all women could be net generators of energy? What difference would it make to their finances and social standing?

Yerevan looked at the rise of space tourism: how might the possibility of looking back on Earth as our ‘common ground’ affect attitudes towards managing local green spaces?

Nis looked at blockchain-based cryptocurrencies: how might this be used to incentivize and accelerate behavior change? Could citizens earn tokens for using bicycle sharing schemes or public transport?

As guest expert, Joost Beunderman of Dark Matter Labs emphasised, “We are designing within the rules, and these rules are no longer valid. You should ask yourself how to change the rules.”

Exploring converging trends and their impacts for citizens widened the realm of possibility for our teams. They began to think outside the box: Kragujevac starting asking how the church could galvanise people around waste management; Chisinau considered reintroducing horsepower; Yerevan envisaged dance-offs in green spaces…

Thinking bold, beyond the confines of our expectations and assumptions, is a rite of passage for experimentation.

Join discussion