We need to understand change to create change. So how does change happen? What does it take for a change process to start? Rodrigo Bautista, Principal Change Designer at Forum for the Future, discusses four lessons from the story of the civil rights movement.

This article was first published by School of System Change here. We are republishing it in celebration of the Black History Month in the US.

A single event or person can not create change alone; their actions and impacts are constantly interconnecting to others. As change-makers, the more we examine the relationship of our work to others, and the more we comprehend why we think and act in a given way, the more chances we have to influence those, and eventually create systemic change. We need to understand the patterns that are around us over time, analyze system structures and seek root causes because that is when transformational shifts can happen. Societal beliefs and attitudes underpin our systems and keep them functioning or malfunctioning.

“Most things disappoint until you look deeper.”

Because change is happening, how can we steer it for more deliberate outcomes? In this story, we identified how a shared purpose combined with creative disobedience, a culture for learning and iterating, and persistence despite the difficulty or the delay, increases our chances to create change. The civil rights movement is an example of this; it was a web of people, ideas and wills that produced change and seeded a new society.

The beginnings of the civil rights systems change.

A well-documented series of events in history is the Rosa Parks arrest and the bus boycott that followed. Parks refused to vacate her seat on a public bus to a white man, precipitating the 1955–56 Montgomery bus boycott, known by many “as the spark that ignited the U.S. civil rights movement”. However, what was behind the event? How does her refusal connect to a larger plan? Who else was part of the so-called “spark”?

Let’s look back. In the autumn of 1944, Recy Taylor left the church in Abbeville, Alabama; she was walking with a friend and her son. A car with six white males approached and stopped the trio pointing towards Taylor. They used guns and knives to force Taylor to board their vehicle. All of them raped Recy Taylor and threatened to kill her husband and little boy if she mentioned the assault.

She broke the pattern and shared her story.

Unfortunately, this story was typical. Recy, with courage, broke the pattern and shared her story, which was printed in newspapers. She also contacted the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Alabama’s chapter. E. D. Nixon, the local president, promised to send his best investigator to Abbeville. That investigator would launch a movement that would change the world. That investigator’s name was Rosa Parks.

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically … No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

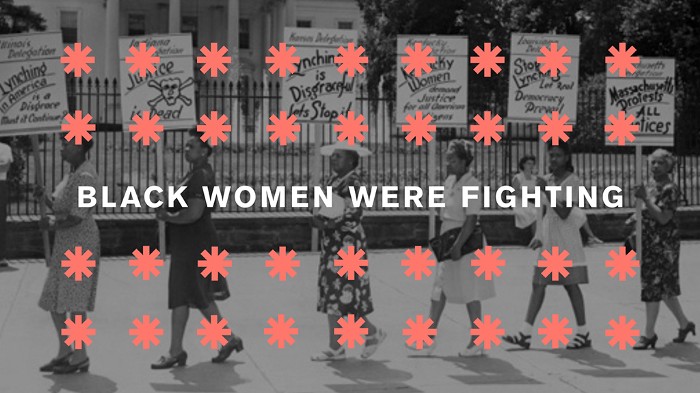

Rosa Parks wasn’t a tired old lady; she was an experienced activist with over a decade of vigorous work. Soon after Park’s arrest, JoAnn Robinson — an educator and activist part of the Women’s Political Council — called for the non-violent bus boycott, which brought the introduction of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. The designed bus civic disobedience intervention and the boycott resistance resulted in a Supreme Court victory, changing segregation law and making it unconstitutional. Rosa Park’s notorious event, her refusal to give up a seat, was not the spark; it marked the end of the beginning of the civil rights movement.

What patterns reinforced the system of white supremacy?

Before 1955, a series of patterns in U.S. society reinforced white supremacy consistently. The kidnapping and rape of Recy Taylor were not uncommon in the segregated south. The sexual exploitation of black women by white men has its roots in slavery. White men abducted and assaulted black women in streets or at their jobs with frightening regularity because they did not get punished.

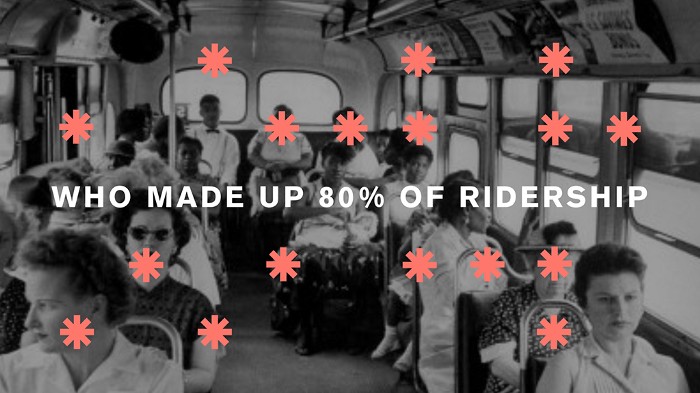

In tandem, the black community was growing tired of the mistreatment they consistently faced when using city services. In Montgomery, the black community made up 80% of city ridership. Many took the bus from the black side of town to the white side of town daily to work in white people’s homes. They were mistreated and abused on the buses.

There had been previous efforts to confront systemic oppression. Claudette Colvin was arrested nine months before Parks for the same action. Another case was the boycott of Green’s grocery store in Montgomery. Sam Green raped Flossie Hardman in 1951, one night when he was driving her home. An all-white jury found Green not guilty. The community organized a boycott; the campaign succeeded in closing the store and established the boycott as a powerful force for justice.

What creates or influences patterns?

“Separate but equal” laws were in place. Segregation formally preserved oppression.

After WWII, African American soldiers that fought for freedom and democracy during the second world war went back to face an internal paradox. They experienced limited liberties and lack of democratic rights, the exact opposite of what the U.S. government preached to the rest of the world. They started moving out of the South and into the North and West by the millions — where they could vote, and continue to advance the cause of liberty.

Simultaneously new connections were made and strengthened: the NAACP local chapters started to connect to black activists in NYC, Chicago, California, and the rest of the country.

Further, increased changes in regulation in the U.S. created more and more clashes on one side perceiving white power being challenged and threatened, and, on the other hand, lack of real equality for all black people.

What assumptions, beliefs and values underlied the system, and held it in place?

The deep-seated purpose of the belief system was the placement of black people beneath whites in every possible scenario. White supremacy ideals ensured that the system structure continued to behave in such a brutal form, coupled with patriarchal power. These two beliefs underpinned legislation such as segregation, pardoned white people’s abusive behavior, and in extreme cases fueled lynchings of black men and rapes of black women.

During WWII, the United States fought against ideas of racial superiority. But when U.S. soldiers of color returned from the war, they were reminded of the racism that existed in their backyards and denied the right to vote (even though it was a constitutional right). The hypocrisy was crushing, but it galvanized African Americans to use it as an opportunity to grow their influence for real equity.

The combination of these events, patterns and beliefs created a new context which provided confidence for scaling up action. The result of the boycott that followed Park’s arrest ended with a supreme court ruling where segregation was made unconstitutional. However, perhaps equally and perhaps more decisive its how they contributed to strengthening the wave of change for the movement. A wave formed by courageous people that persevered for another decade to continue the cutting and knitting of a more equal society.

What are the learnings from this systems change story?

1) You are not alone. Often successful stories celebrate one person or one event, missing depth or not mentioning the group of people surrounding that individual (i.e. a node in the system) that were part of creating change. Who are the nodes (people and institutions) in your system? How are you connecting with them? How is their practice is similar and additive to yours?

2) Open orchestration. By having a clear intention, we start to tap and define where we see systems change is needed. Being open and flexible about how change manifests grows the chances of success. As we know, change is a constant, and at a certain point, the circumstances for action align or intensify to create the calculated impact you aim to achieve. Before the NAACP could mount the court challenge, they needed someone to voluntarily challenge the bus seating law and be arrested for it. E.D. Nixon carefully searched for a suitable plaintiff. After being called about Parks’ arrest, E.D. Nixon went to bail her out of jail. He arranged for Parks’ friend, Clifford Durr, to represent her. After Parks’ arrest, JoAnn Robinson and E.D. Nixon called local ministers to organize support for the boycott, including a young minister newly arrived from Atlanta, Georgia, his name: Martin Luther King Jr. When do you need to plan and when do you need to go with the flow? How open are you to adjusting your plans and use a new breeze or create the breeze for someone else?

3) Reframing power and courage. The role of black women is critical for the success of the civil rights movement; however, in mainstream media and culture, their role in history is often overlooked. We tend to look to traditional power as holding the keys to change, but here it was a marginalized group that found their power. All of us are not only liable to be fearful; we are also prone to be afraid of being afraid; they were not really afraid. They were just afraid of being afraid. What power are you holding and how courageous do you need to be? When we share success stories, what and who are we leaving out? What else are we missing in today’s efforts to create a flourishing planetary society?

4) Learn, iterate and persevere. There were previous boycotts, there was the strategic use of media, and prior law cases presented to State and Federal Courts pushing to eradicate segregation. Across all of those actions, change-makers were actively learning, trying new interventions and discovering how to be more effective. Rosa Parks, eleven years after arriving at Recy Taylor’s house was tired, tired of giving in, and she was ready with many others to apply previous learning to a bigger movement for the next ten years. What can you learn from your practice and from others? What has been done before that succeeded and has the potential to scale? How do you personally recharge and regenerate your practice?

Finally, as I write this, on one hand, I would like to think that society globally after more than half-a-century has eradicated racism, but the reality is different. I am Mexican with more than ten years of being a migrant, and it is evident to many that the rhetoric of racism and white supremacy has grown since 2016, I experienced that change. On the other hand, thinking about the tools we have available and much of the progress made, and how people are putting themselves on the line for change, I am eager to carry on. Today as we start the new decade, I ask you to reach out and join the School of System Change, because we need to learn from each other. We need to work together so that collectively we can change how power and privilege design societies that are free, democratic and support everybody on this planet to flourish.

Join the conversation #systemschange.

The #systemschange animation was produced by Forum for the Future using the Iceberg model for analysis, in collaboration with Glider and Danielle L. McGuire and is based on her book At the Dark End of the Street Black Women, Rape, and Resistance — a New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power.

Read next:

- The full series of stories of change case studies

- About our application of futures in the fashion industry: Fashion Futures 2025: case study – exploring how climate change, resource shortages, population growth and other factors will shape the world of 2025 and the future of the fashion industry within it.

- How our live research functionality helped us drive a futures exploration into how a regenerative energy system could work – Live Research case study – Living Grid in partnership with SmartestEnergy

- A case study on applying futures and systems expertise to understand the future sources of vulnerability for children and adolescents in South Asia and how they might address them – South Asia Futures: case study

Join discussion