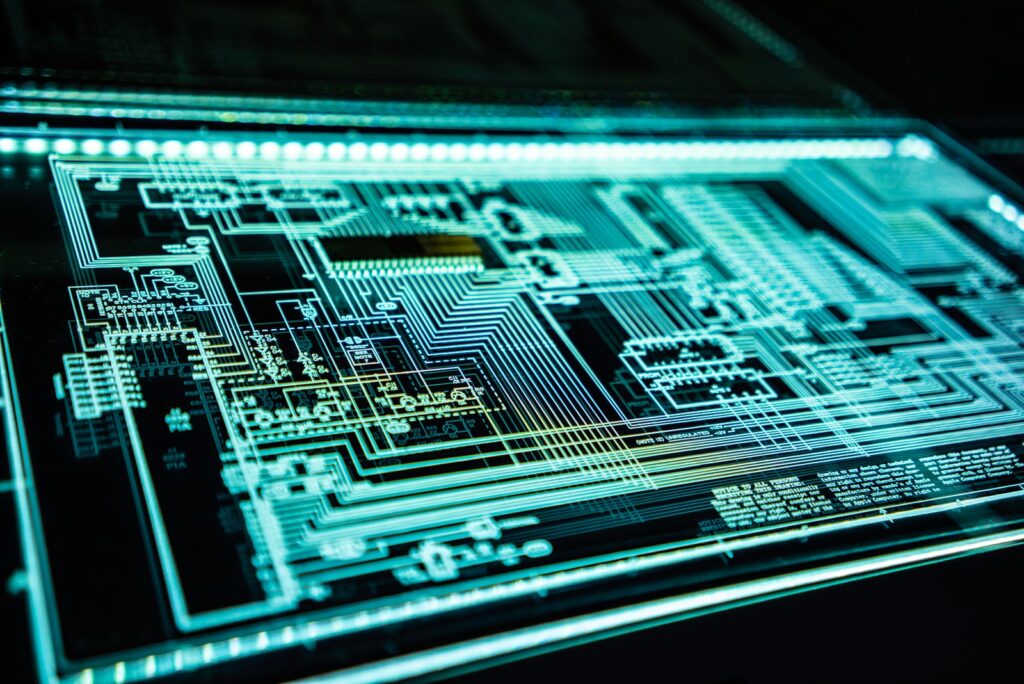

The bottleneck in chip supply is spiralling into a crisis with systemic implications. Joy Green looks at the cluster of signals that is now emerging, and has the potential to shape the global outlook for the decade ahead.

A dip in production of computer chips that began with pandemic-related production cuts has now spiralled into a chronic crisis that could last as long as two years.

As the pandemic took hold globally last year, demand for chips was expected to drop, as major car manufacturers cut their orders, and chip manufacturers switched and cut production accordingly. However the boom in screen time and home electronics during national lockdowns actually boosted demand for chips, and car orders rebounded much sooner than expected, causing a global shortfall. This was then exacerbated further by a fire in a semiconductor facility in Japan, and the cold snap in Texas which hit chip production by Samsung and others.

In normal industries, recovering a dip in production is fairly straightforward. However the production of advanced semicondutor chips is a very costly, complex and lengthy process that cannot be ramped up quickly; new chip fabrication facilities take years to build, cost billions, and become obsolete quickly. As a result, only a few companies are able to cope with the brutal economics involved, with the result that global supply is dominated by just two giants, TSMC in Taiwan and Samsung in South Korea. IBM’s president recently said that he now expects the shortage to last two years.

The shortage is already hitting car manufacturers and could potentially slow the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) by affecting production numbers. However many other industries will also be affected as the shortage drags on, from household appliances and consumer electronics to the actual process of manufacturing itself. Inflation may start to increase as production falls, complicating recovery plans as the world tries to rebound from the economic impacts of the still ongoing pandemic. And of course ultimately every part of modern economies is reliant on computing power, from healthcare to finance.

Self-sufficiency or international co-operation?

An important geopolitical element is also emerging, as 92% of the world’s most advanced semiconductors are produced in Taiwan by TSMC. This is a massive headstart that will take any other country years to catch-up on. But it is becoming clear what a bottleneck this can be for the global economy, to have production so tightly concentrated in one place. It also sharpens the technological and political rivalry between the US and China. Both countries were already increasing their political and military focus on Taiwan, and both are also now scrambling to build self-sufficiency in these essential components for modern economies, in a disconcerting echo of the 20th century geopolitical fixation with oil production that produced client states, resource shocks and extended conflict.

However a retread of those dynamics are not the only possibility. Analysts who map the semiconductor value chain are calling for a different solution. Jim Lee from MERICS says, “The smart way to build resilience across the global supply chain is greater coordination across different countries, rather than chasing self-sufficiency with the huge risk and expense that would involve.” In other words, a move towards international co-operation needs to trump the siren calls of nationalist self-sufficiency. There is an interesting wider symmetry here with the pandemic itself, where it is similarly clear that the fastest successful ‘exit’ for the world will require international co-operation on vaccine manufacturing and distribution, and a move away from the temptations of vaccine nationalism and the illusion of self-sufficiency. The choice of exit route for this computer chip shortage has wider implications than just manufacturing, and could be a shaping factor for the global outlook for the decade ahead.

Read next:

Join discussion