We know our current economic system is no longer fit for purpose. It continues to value profit over people and planet – but there are signs of new models emerging. Charlie Thorneycroft, Forum’s Senior Change Designer, and Caroline Ashley, Global Programmes Director, explore what innovations are bubbling with potential to transform how we think and feel about our economy.

In our daily work attempting to address critical global challenges and stretch the ambition of sectors, companies, partners and ourselves, we are constantly hitting up against the constraints of the current economic model and the pursuit of growth at all costs. We cannot achieve many of our ambitions unless the goals of public policy, business models and financial flows are all rewired to value human wellbeing and environmental regeneration at their core.

At Forum for the Future, we are constantly scanning disruptions that are bubbling in the niche that have not yet mainstreamed. New ideas from the margins will be invaluable in shifting assumptions about how our economy works and building new models. For example, most of us assume that money is fundamentally a store of value that enables us to trade with anyone; that investors naturally seek strongest financial returns, and that intellectual property rights are necessary to incentivise innovation.

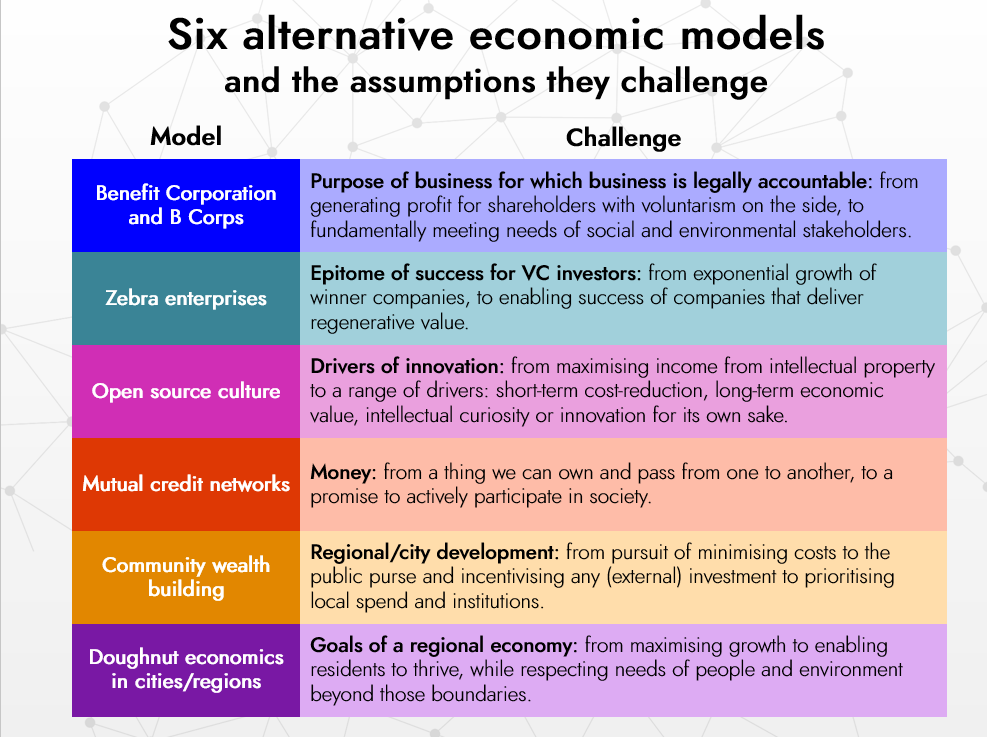

Here, we explore six innovations that are challenging mainstream economic assumptions, covering business models, finance, intellectual property, money, and regional economic policy. None of these ideas are particularly new; indeed, some of them have been around for hundreds of years. However, each of them challenge the current economic model, which is based on the logic of efficiency, extraction, and exponential growth.

We do not know which, if any, of these will scale or become intertwined with other innovations. However, they do appear to be gaining traction in new and surprising ways. What is certain is that the pace of innovation is picking up and being considered from more mainstream players. Greater dislocation and innovation in our economic models should be expected, and indeed, welcome.

Benefit Corporations and B Corps

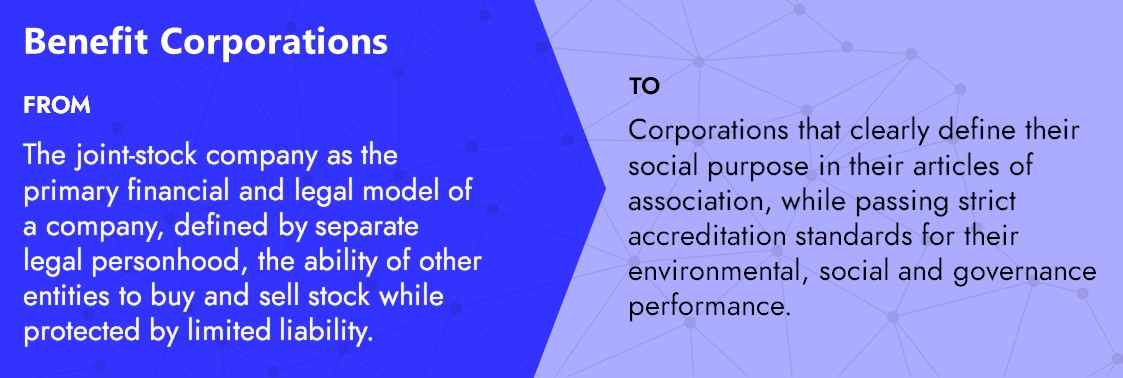

Benefit Corporation is a legal structure for companies to enshrine a social purpose in their articles of association and be held accountable for strict standards, thereby challenging the notion that companies must maximise value for their shareholders, rather than be driven by other interests, including the environment and society. B Corps is the voluntary certification that is available in any jurisdiction.

The legal structure of the joint-stock company created the ability and incentive to pool small amounts of capital from a large number of people to invest in corporations that are able to achieve economies of scale. However, this legal structure effectively separated owners from managers, creating a need to re-align their interests through tying executive pay to share prices. Corporate governance has since been dominated by a short-term focus on share price movements over the long-term success of the corporation and the interests of wider stakeholders. Meanwhile, there has been no mainstream means of investing long-term, while short-term thinking continues to dominate corporate culture, and thereby mainstream financial markets.

On the other hand, Benefit Corporations are legally required to balance the interests of a range of stakeholders and be accountable for their social and environmental performance through regular auditing and accreditation. All stakeholders can then engage, divest or even sue corporations for breaching their articles of association as a result.

The US is perhaps currently leading the way in this regard, with Benefit Corporation legislation passed in 31 US jurisdictions. In the UK, the Better Business Act movement is striving to amend the Companies Act to enshrine these principles in UK law. The B-Corp movement has risen as a voluntary scheme that does not require legislation. Fast Company reported in 2020 that more than 3,500 companies have achieved B-Corp accreditation, passing a 200-question assessment that judges performance across governance, environment, workers, customers and community. In 2020, two B Corporations went public, and six large multinational companies began the journey to qualify for B Corp status.

By enshrining public benefit through Benefit Corporations, business behaviour that seeks profit at the expense of social value is much more readily challenged and changed, and moves beyond voluntarism.

Zebra enterprises

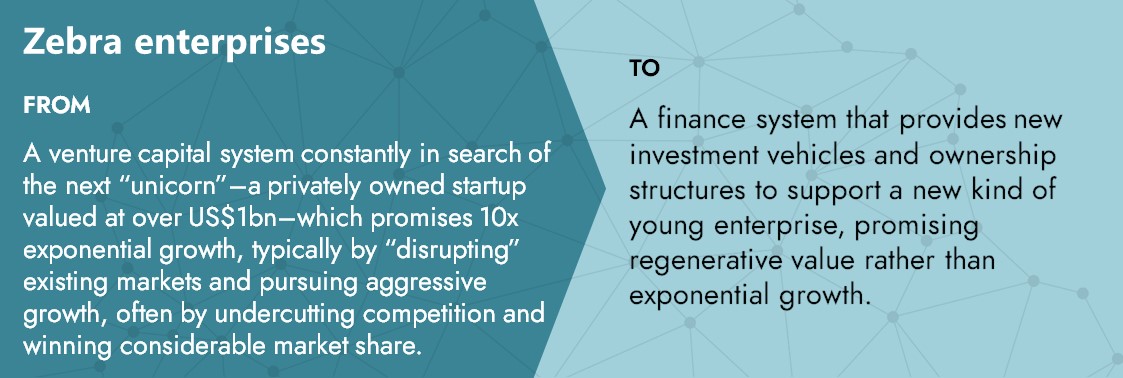

The concept of ‘Zebras’ in venture capital seeks to replace that of Unicorns, pitting companies that deliver regenerative value as the epitome of success in investment, rather than exponential growth.

While the venture capital system may have its roots in the whaling industry, it is the unicorn that has since become the emblematic metaphor of the industry. This model has given us Facebook, Uber, Airbnb, WeWork, and the like – companies that are rewarded for delivering exponential growth regardless of the social and environmental impacts of that growth. Meanwhile, companies that are disruptive in ways that enhance social and environmental outcomes but hold less prospect of exponential growth attract less capital.

Shifting this system could instead foster so-called ‘Zebras’ – companies that are black and white; both profitable and purposeful; mutualistic, working together to support the communities they serve; and have stamina, able to think and plan long-term if given the right enabling ecosystem.

The Zebras Unite movement was started by a series of blog posts in 2016, sparking the inaugural gathering of a Dazzle (the collective noun for a group of zebras) of 250 investors, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists in San Francisco. The group now has 25 chapters internationally providing support, advice and funding to ‘zebra enterprises’ around the world.

Rather than simply accepting the commonly-held precept that 90 percent of start-ups must fail, Venture Capitalists could focus on creating the right enabling ecosystem and financing for these zebra enterprises to flourish.

Open source culture

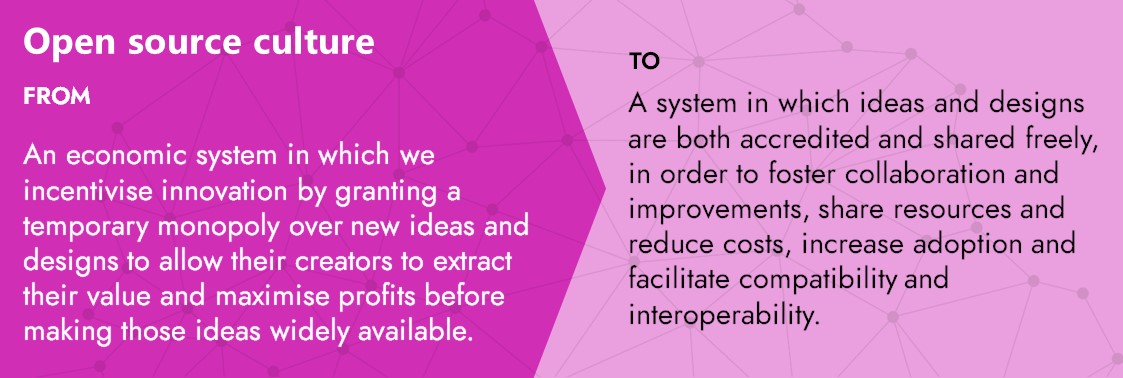

Challenging intellectual property regimes to promote an open source culture would put value over profit as the driving force behind innovation.

One of the effects of the current intellectual property regime is perpetuating a model that creates value by locking-in consumers. With significant costs of switching to competitors, customers become dependent on a particular company for goods, services, repairs and replacements. For example, a printer manufacturer may sell the printer at cost in order to make significant margins on cartridges. Intellectual property rights prevent other companies from selling compatible cartridges or spare parts for the printer. This model perpetuates the phenomenon of planned obsolescence – preventing other companies from designing spare parts and modifications drives obsolescence. This model is therefore a significant barrier to the Right to Repair movement and the circular economy.

In practical terms, an open source culture can enable a sharing and repairing economy, creating new opportunities to either repair or build upon existing products in innovative ways. Open-source cultures also harness a broader range of incentives to drive innovation, from short-term cost-reduction, creating long-term economic value, and to intellectual curiosity and innovation for its own sake.

Open source culture has developed fastest in the tech sector. Mozilla were early pioneers of open-source software development, producing a range of freely available digital products. Software developers from around the world collaborate in a decentralised and asynchronous fashion using Github, a platform that allows developers to branch code, make suggestions for improvements and merge changes with the master version.

This culture is also beginning to bleed into hardware. The Open Source Ecology Movement has published the designs and instructions for constructing “50 different Industrial Machines that it takes to build a small, sustainable civilization with modern comforts”, selected with the intention of enabling the production of other machines in a self-replicating, regenerative cycle. These modular designs can be built, repaired and improved on at a fraction of the cost of commercial models.

As younger generations become fluent in open source culture, it will begin to influence how we work, organise, plan and innovate.

Mutual credit networks

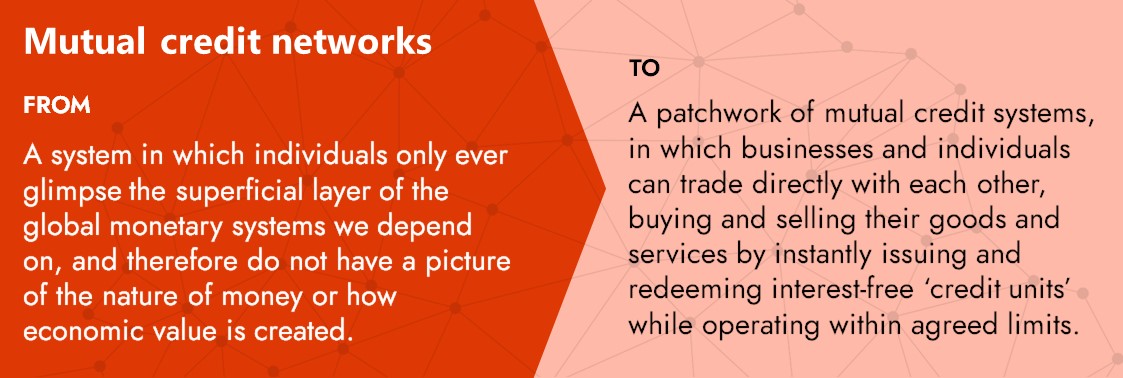

Mutual credit systems turn individuals from being simply users of money into issuers of money, which helps to drive a mindset shift in how we view money – not as an object or commodity we accumulate in a bank account but as a promise to actively participate in society.

Commercial banks create 97 percent of the money in circulation in the form of loans, or IOUs. While it is possible for individuals to transfer cash and issue loans between one another, in practice there is almost no infrastructure to facilitate these activities outside of the banking system.

This has resulted in global monetary systems that provide us with enormous benefits. However, it also restricts access to credit in places where large populations do not have access to banks, and to small and medium sized enterprises – especially when banks’ confidence in the economy is low. It may sound surprising but in practice, people technically loan their money to a bank when they hold it in an account – all the money in our bank accounts takes the form of credit, or IOUs. This fact is obscured from us because we rarely see or think about the other side of the bank’s balance sheet. Yet, this system encourages us to think of money instead as if it were an object or commodity we collect, with its value tied to its scarcity or the scarcity of the commodities we can buy with it.

Mutual credit is a form of alternative money, but unlike a currency, it cannot be exchanged outside of the network for legal tender or other currencies; nor is it a form of commodity or token like Bitcoin, where its value is tied to the notion of scarcity. Instead, the credits are in effect promises to contribute goods and services back to other organisations in the network.

Several working mutual credit systems already exist today. The WIR Bank in Germany was founded in 1934 following the Great Depression and is a type of hybrid mutual credit system that today has a ten figure turnover and more than 60,000 members. The SardexPay mutual credit network in Sardinia was formed in 2009 following the financial crisis. Today, it has 3,200 business members and a transaction volume of €43m.

One of the trade-offs with mutual credit systems is that they are built on trust, and therefore its scale is limited to specific local communities or business networks, covering limited goods and services. There are, however, attempts to link these networks together to form a credit commons. For example, the Open Credit Network in the UK is developing an open-source software that enables local mutual credit systems to link to one another, while Trustlines and the Serafu Network in Kenya are building similar systems based on blockchain technology. In 2020, the Serafu Network reached nearly 90 million Shillings (~US$900,000) worth of trading between 30,000 users in Kenya for basic needs, in over 300,000 transactions on a blockchain.

In practical terms, these systems improve access to interest-free credit to those who cannot meet the lending requirements of banks. It encourages the circulation of credit within the network, which responds flexibly to the level of demand and available resources in the local economy. Most pertinently, mutual credit systems change the way we think about money: from a thing we can own and pass from one to another, to a promise to actively participate in society. It enables individuals to see themselves as part of a network, issuing IOUs to obtain goods and services now, in return for goods and services in the future.

This shift from being a money user, to money issuer could help to drive a mindset shift to seeing the real source of economic value as originating in the community working together to turn resources into things we need and want.

Community wealth building

Community wealth building is an approach to economic development that uses local institutions to promote the circulation of wealth within communities and to empower local economies, relative to global capital.

The current dominant system drives competition between regions for investment, putting downward pressure on standards, wages, and regional tax take. It can result in an area being over-represented by large corporations with little connection to the local economy. These companies are owned and operated in the interests of distant shareholders rather than local stakeholders, meaning much of the wealth generated in local economies flows out in the form of profits and dividends. In return, communities are offered jobs and ‘efficient’ prices for goods and services.

In contrast, the community wealth building approach challenges the assumption that competition alone delivers the most efficient outcomes. Procurement rules of anchor institutions need to consider social and environmental values alongside price, and recognise the importance of collaboration alongside competition. The result is increased circulation of wealth within communities, while building a diverse ecosystem of locally-owned small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and promoting fair employment.

This model has already been successfully applied in Preston, England. The application of the community wealth building model in Preston resulted in the proportion of spending by the six anchor institutions in the local Preston economy increased from 5 percent to 19 percent between 2012 and 2017, while spending in the Lancashire region increased from 39 percent to 81 percent. In 2016, Preston was ranked as the best city in north-west England to live and work in, beating both Manchester and Liverpool. The new mayor of Chicago recently proposed a US$15m community wealth building pilot, which she said “will create a new economic development program to promote local, democratic and shared ownership and control of community assets.”

The aim of this movement is not to turn our back on the benefits that come with large multinational corporations. Instead, it aims to restore the balance of power between local communities and SMEs, and global capital.

Doughnut economics

Doughnut economics reframes the goals of the economy away from growth maximisation to meeting the needs of all, with the boundaries of planetary health. Cities and municipalities such as Amsterdam are proving to be the ideal scale for testing this new framework.

In the current system, cities and regions develop unequally and at the expense of others, with social and ecological impacts that extend far beyond their borders. The Doughnut Economics approach requires an analysis of what it would take for the people and environment to thrive within that place, while respecting the wellbeing and health of people and environment outside of that place.

The city of Amsterdam has become one of the first real testbeds of the doughnut economics framework. In 2019, the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group commissioned Kate Raworth to analyse where Amsterdam stood in relation to the doughnut, and in 2020 the city decided to formally adopt the framework in their policy decisions. There is evidence that the framework has begun to shift the mindsets of public officials, which is starting to influence their decision making. For example, at the start of the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020, the city collected and refurbished 3,500 laptops for residents without digital access rather than purchasing new ones. According to one city official, this choice reflects their new way of thinking.

Several other cities are now following Amsterdam’s lead, from Copenhagen and Brussels, Birmingham and Manchester to Sao Paulo and Kuala Lumpur. Doughnut Economics even featured in an episode of UK soap opera Eastenders, signalling that the ideas are truly starting to enter the mainstream consciousness.

What do these innovations mean for our future?

While each of these disruptors may be piecemeal, they are gaining traction and challenging some of the fundamental tenets of neo-classical economics, which current economic models are built on: the idea that maximising growth, cutting costs or attracting external investment should be the goal driving city or regional planning; that innovators must patent and protect their ideas to secure gain and provide incentives, that businesses’ first duty is to shareholders; the idea that money is something you store, rather than a commitment to act. All of these principles are foundational in our system.

In exploring these alternatives to our current systems, we begin to reckon with the possibility of change, and the potential to overcome the barriers we so often face in our everyday work. Our economic assumptions are not fixtures. Just as the Amazon rainforest may become a net emitter or Atlantic currents may collapse, equally, basic principles of current economics may change.

To quote the late economist and anthropologist David Graeber: “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make and could just as easily make differently.”

But beyond just possibility, these alternatives also reveal the desirability of change. We need economic fundamentals to change. The obsession with growth as the end in itself, rather than just a means to support wellbeing, with environmental resources as an input, not systems to regenerate, has to change. We take optimism from the growth of these alternatives that such change is possible.

Further Reading:

Benefit Corporations

- Shareholder Capitalism (NEF)

- A Free Market Manifesto That Changed the World, Reconsidered (New York Times, 2020)

Venture Capital and Zebras

- Is Venture Capital Worth the Risk? (The New Yorker, 2020)

- Sex and Startups (Zebras Unite, 2016)

- Zebras fix what Unicorns break (Zebras Unite, 2017)

- Where unicorns fear to tread — building businesses that are better for the world (Zebras Unite, 2020)

Open Source Culture

- Here’s the truth about the planned obsolescence of tech (BBC, 2016)

- Are the right-to-repair laws fair? (Raconteur, 2020)

Mutual Credit

Community Wealth Building

- Plugging the Leaks (NEF, 2001)

- Community wealth building: a history (CLES, 2020)

Doughnut Economics

- Doughnut Economics (Kate Raworth)

- Amsterdam Is Embracing a Radical New Economic Theory to Help Save the Environment. Could It Also Replace Capitalism? (Time, 2021)

Watch this space

The next in our Future of Sustainability: Looking Back to Go Forward series sees James Payne, Forum’s Associate Director for Transformational Strategies sharing insights to define the ‘next edge’ of sustainability for businesses: adopting a just and regenerative mindset. How does the response of business to the big sustainability challenges we face measure up to what is needed to make a more hopeful future possible?

About the Future of Sustainability: Looking Back to Go Forward

Produced by international sustainability non-profit, Forum for the Future, the Future of Sustainability: Looking Back to Go Forward is a unique opinion and commentary series set to explore lessons learned from the last 25 years in the sustainability movement and what they mean for the future.

Based on new and exclusive insights from diverse voices across the sustainability movement, we’ll examine where we have succeeded and where we have failed in creating real change. We’ll consider how the world is responding to today’s multifaceted challenges and opportunities, and what pivots might be needed if we’re to deliver at scale and pace. Lastly, we’ll look forward – exploring how we can reframe the goals of the system, reset our ambition, and encourage the adoption of new mindsets and approaches critical to creating what’s really needed: a truly just and regenerative future.

With thanks to our partners

Looking Back to Go Forward was made possible thanks to the generous support from our partners: Laudes Foundation, GSK Consumer Healthcare, Target, M&S, Capgemini, Bupa, 3M, the Cosmetic Toiletry & Perfumery Association (CTPA), Burberry, Olam Food Ingredients, and in particular our headline sponsor, SC Johnson

Join discussion