Listen out:

‘The American Jobs Plan will unify and mobilise the country to meet the two great challenges of our time: the climate crisis and the ambitions of an autocratic China.’

So said Joe Biden’s Press Secretary on 31st March, unveiling his new American Jobs Plan – in all its $2.2tn glory!

The Biden/Harris Administration marked its 100th day in office on April 30th. It’s been an utterly remarkable 100 days, shifting the US from its status as climate-trashing pariah-in-chief (under Trump) to proactive champion leading the charge on global climate diplomacy in the run-up to COP26 in Glasgow in November. And doing that far more effectively, in my opinion, than COP26’s formal co-Presidents in the UK and Italy. Here’s a quick summary:

1. The team

Biden and Harris have appointed a heavyweight team (from John Kerry as Climate Envoy through to literally dozens of senior appointments across the whole of the Administration). They’re all experienced operators with deep knowledge of ‘working the system’. 2021 is the key year; 2022 is back into adversarial politics with the mid-term Elections coming up in November.

2. Executive Orders

Biden’s first day in office saw a blizzard of Executive Orders designed to undo some of the damage done after four years of Trump in the White House. Recommitting to the 2015 Paris Agreement got all the headlines over here, but his signal to all Federal Departments and Agencies that their (vast!) procurement budgets would need to prioritise low-carbon investment mattered at least as much.

3. The American Rescue Act

Biden’s $1.9tn stimulus package, in response to the economic fallout from the pandemic, is the closest thing to an old-fashioned Keynesian investment programme that the world has seen for a very long time – not just in terms of the direct payments made to US citizens, beefed-up unemployment insurance and new childcare benefits, but through significant investments in public services, including $30bn devoted to public transport and $350bn for state and local governments to repair their broken-down infrastructure (water, sewerage, broadband and so on).

4. The Leaders Summit on Climate (April 22nd – Earth Day)

The President used his platform here to declare a new target of a 50%-52% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2035, on 2005 levels. He could (and perhaps should) have been more ambitious, but this puts the US right back in the top tier.

5. The American Jobs Plan

As already mentioned, this is another $2tn blockbuster, focusing not just on physical infrastructure (including grid upgrades, clean manufacturing, tax credits for renewable electricity, public transit and rail, EVs and so on), but on digital infrastructure and social infrastructure (with a particular emphasis on carers and on improving children’s wellbeing). It’s an inspiring ‘declaration of intent’, but there’s a long way to go before it clears through the Senate.

This is not Joe Biden’s ‘Climate Plan’ as some critics have claimed. Nor is it some all-encompassing Green New Deal, as some had been hoping for. It’s much smarter than that, with an unapologetic emphasis on ‘jobs, jobs, jobs’, speaking as powerfully to blue-collar workers and to rural communities as to the Democrats’ traditional metropolitan constituencies.

That’s what Biden’s been up to. What’s China been doing during the same time?

China’s economy is back in full-on growth mode, and investment in new coal-fired power stations is as strong as ever. The International Energy Agency has warned that its emissions in 2021 will be higher than ever, and that there is literally nothing by way of a roadmap to show how China intends to achieve its target of becoming a Net Zero economy by 2060.

We have to understand the deep contradiction at work here.

1. In terms of the global economy, China is as intent as it has ever been on dominating what will soon become the multi-trillion-dollar green tech sector. This appears to have little if anything to do with concerns about climate change, and everything to do with the ‘made in China’, innovation-driven game-plan captured in its latest Five Year Plan. China doubled its already huge investment in renewables in 2020. It’s installed far more wind power and far more solar power than any other nation on Earth. Five out of the 10 largest wind power companies in the world are Chinese; nine out of 10 of the world’s largest solar companies are Chinese – and it’s this concentration of manufacturing and R&D muscle that has so dramatically driven down the cost of both wind and solar year after year after year.

2. There is a clear contradiction here, with shocking environmental damage continuing to mount through China’s massive mining operations (for coal, metals, rare earths and so on). And that’s the other side of this story: the cumulative costs of 30 years of more-or-less unregulated economic growth, based on cheap coal, are quite literally incalculable.

There’s much talk of China’s ambition to reduce dependence on coal – as there has been for years. Most of it is complete nonsense. Its existing commitments are as minimalist as they can get away with: emissions peaking in 2030 (i.e. going up and up until then); modest reductions in the amount of CO2 emitted per tonne of output; and a ‘Net Zero economy’ by 2060.

One can also see this contradictory dynamic playing out in the world of Electric Vehicles – which is really a story about batteries. The Chinese are already responsible for two-thirds of global lithium-ion battery manufacture; the USA just 10%. In terms of the raw materials required for battery manufacture, the Chinese now control between 50% and 70% of global supply. And with all this industrial muscle deployed so aggressively, they’ve been almost as effective in bringing down the costs of battery production (down 60% over the past five years) as they have been with solar panels.

And batteries are all about lithium. China (or, rather, Tibet) may not have the largest reserves of lithium – that’s Chile – and it’s not even the largest producer of lithium – that’s currently Australia. But it soon will be. Use of lithium-ion for batteries in China is projected to increase tenfold by 2030, and Chinese companies are expanding the mining and extraction of lithium from Tibet at an astonishing rate, causing horrendous environmental pollution in some of the world’s most sensitive (and most sacred) places.

The extraction of lithium represents just a small part of China’s continuing exploitation of Tibet’s natural resources – and a small part of its subjugation of the rights and the culture of Tibetan people. This seventy-year horror story is now compounded by its ruthless oppression and ethnic cleansing of the Muslim Uighurs in neighbouring Xinjiang. All this poses a serious dilemma for Western companies, given that almost every solar panel sold in the EU includes some polysilicon from the Xinjiang region – 45 per cent of the global supply of high-grade polysilicon comes from Xinjiang.

We have to be honest here. China’s economy is by far and away the greatest single threat to any prospect of a stable climate in the future. We’ve cut them a lot of slack simply because they’ve made it possible for the rest of the world to start getting out of fossil fuels far faster than anyone thought possible – and far faster than they have any intention of doing themselves. But we simply cannot go on turning a blind eye to the abhorrent environmental and social consequences of these economic and technological breakthroughs.

We shouldn’t underestimate the geopolitical implications of all this. I would argue that this is now the biggest proxy war going on in the world today.

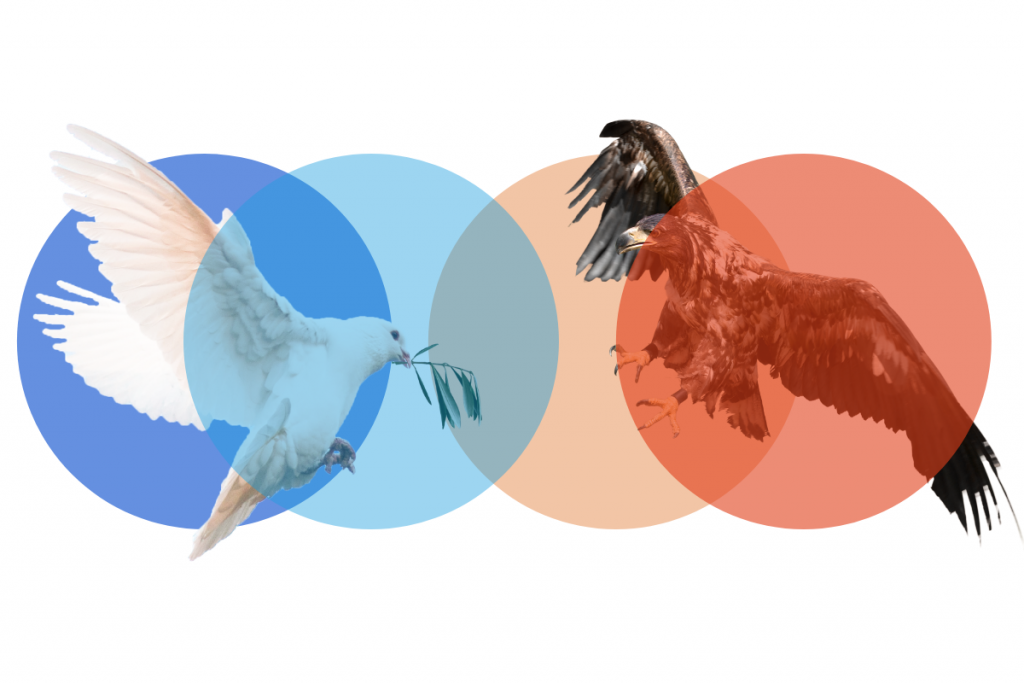

America is late to the party – at least 10 years late – and is in catch-up mode. But the current administration has clearly recognised that this is indeed a war. There are two schools of thought here – with doves and hawks battling it out.

The first is to try and keep climate diplomacy apart from all the other issues where China and the US are in direct competition with each other – to ‘compartmentalise’ it, and be ready to make concessions to ensure China’s cooperation – even though China itself certainly doesn’t see things in those terms.

The second is to compete head-on with China, to call out its planet-threatening energy inefficiency, its massive overproduction of steel and concrete (essentially to flood global markets), and its hugely damaging Belt and Road initiative. A growing number of hawks believe this is the better way forward, calling for a coalition with the EU to establish ‘carbon border taxes’ on all imported goods from China based on relative carbon footprints. This, it is argued, would force China to address its reckless use of coal, whilst helping to bring jobs back to both the US and the EU.

For me, the hawks have it.

Read next:

Signs of the times In these times of systemic shifts and discontinuity, Joy Green reflects on the signals and patterns of the last couple of months. What are we seeing with systemic implications?

Exploring transformational governance together Governance can be transformational. When we set our sights on changing the world, we also know that governing well goes beyond preparing our own organisation, network or movement for the future. How do move beyond tweaking the way things currently work and apply governance to transform the ‘systems’ that operate in our society that maintain injustice, oppression and inequality (such as race, patriarchy and class)? Written by Transformational Governance Stewarding Group – Asif Afridi (brap), Joe Doran (Lankelly Chase), Jasmine Castledine (School of System Change), Kate Swade (Shared Assets), Louise Armstrong (Forum for the Future), Sarah McAdam (Transition Network)

The computer chip shortage has wider implications The bottleneck in chip supply is spiralling into a crisis with systemic implications. Joy Green looks at the cluster of signals that is now emerging, and has the potential to shape the global outlook for the decade ahead.

Join discussion