We need time to reflect on our shifting cities.

In 2008, for the first time in human history, more than half the world’s population was living in cities. Come 2018, it was 55% and the UN forecast it would rise to 68% by 2050. But 2020 has hung large question marks over much of the rationale for urban living. As cities wrangle with this existential crisis, we have the opportunity to rethink their role and the form they take. How much should they feature in a sustainable and equitable future, and how they could be different from today?

Last year’s logic

One of the assumptions behind both urbanisation and urban design is centralisation: the efficiency and productivity gains of hubs for particular activities. One structural outcome of this was the tendency to work in one area and live in another. Since the industrial era, air pollution has nurtured the aspiration of a home away from chimneys and congestion, while the fear – and in some cases reality – of crowding added to the attraction of larger properties and gardens in commuter belts. Centralised services aimed to serve greater numbers, causing an urban-rural divide in the provision of health, education, information and digital services.

City centres then became desirable as places to meet – for business and pleasure. The assumption at play here was that face-to-face is not just best but necessary; that events of any consequence (commercial, cultural, political, social) take place where people are. Researchers at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU) recognise this as a driver for young technocrats moving from rural to urban areas across the world: “Proximity and opportunities for interaction are deemed necessary to foster creative ideas and inventions“, while “rural-to-urban migration has been synonymous with upward mobility”. And so it became more desirable to live close to where the action is, boosting the prices of inner city properties.

It’s too early to say whether these assumptions have been uprooted for good. But let’s remember that we are not just observers of changing trends in how we live, but creators of them. The rapid, sudden shifts we’ve seen this year call on us to ponder what sort of fallout we want: is the same set of assumptions really going to serve us in reaching the SDGs, particularly via a Just Transition?

New patterns

Already, we’re seeing new structures and different patterns of behaviour emerging on the ground. Which of these do we want to keep and cultivate?

One big winner this year has been digital technology. The lifeline of industries such as retail and conferencing, it has enabled a swift transition from centralised exchange hubs (malls, supermarkets, conference centres) to online exchange. This has also enabled new players to participate, while highlighting the urgent need to overcome digital divides.

More from this author:

Bring back the human: how working culture can support transformation

by Anna Simpson

Many believe social distancing has changed our working habits for good, calling into question the need to live within a viable commute of your workplace, with the potential to breathe new life into smaller towns and rural areas. There’s a strong case for redesigning inner city spaces, such as offices, to support mixed uses – perhaps helping to rescue some arts organisations and small-scale services that haven’t been able to hold onto physical assets. This can be crucial to supporting diverse cultures and economies, and countering monopolies.

There’s also growing recognition of the need for safe, accessible public spaces to tackle a whole range of challenges — cramped spaces, poor lighting, digital exclusion and domestic violence — that are exacerbating social divides.

Shifting aspirations

Inclusion is a key driver for the decentralised ‘Paris en commun’ vision of Mayor Anne Hidalgo, in which any city dweller should be able to reach their work, essential services such as healthcare, schools, parks and shops, as well as social and cultural hubs, within a 15-minute walk from home. What impact could this have on the social fabric of cities? Will it overcome or exacerbate tensions, not least in Paris, where the have-nots are pushed into the back-of-beyond? Urban developers Arup also see a future in decentralised cities, increasing their resilience by reducing the single points of failure.

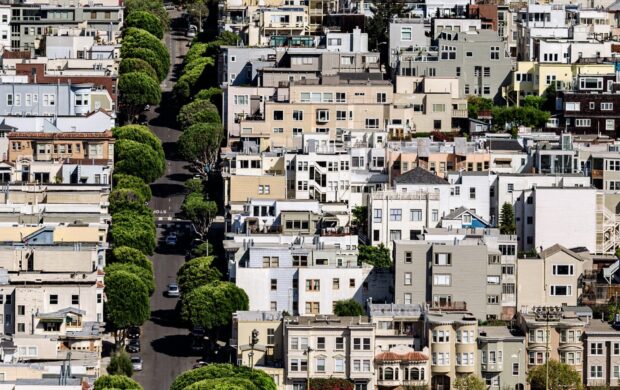

Photo by Barthelemy de Mazenod on Unsplash

Meanwhile, some major cities are seeing reverse urbanisation, particularly as temporary workers leave — their unprotected informal jobs hardest hit by social distancing measures and closures to contain the virus. A study of returning migrants across India, by consulting firm MART, found that one in four do not plan to return to their cities, and will instead try to relocate to nearby towns “because they now have a skill that might get them less money than in the cities but more than in the village”, explains Pankaj Mishra, MART’s Head of Research.

The NTU researchers spot an opportunity to manage the vulnerabilities of centralisation and urban monopolies, across the global South: “a network of smaller, self-sufficient, and intelligent townships, or rural areas enhanced with digital infrastructure, proper water treatment and sewage systems, and reliable energy supply (including renewable energy) could be the answer to a more sustainable and stable future.”

Sustainable urban solutions, from cycling to rooftop farming, have also gained support, as COVID-19 exposed our over-dependence on food imports and supermarket stocks, and highlighted the advantages of combining a breath of fresh air and some exercise with personal mobility.

Emerging viewpoints

What new perspectives might be crystallizing, that could offer new foundations for our future cities?

One is the value of connection. It’s not just that social distancing has shown us what social creatures we are. The crisis has demonstrated the vast importance of cross-sector partnerships and collaborations across government and civil society (a major factor in Taiwan’s success) to our resilience. Take Brazil, where the ten largest informal settlements have established a G10 Favelas network to provide medical supplies and health staff, and collaborate on shared ambitions for socio-economic development.

Sao Paulo, Brazil

Photo by Danilo Alvesd on Unsplash

There’s also an increased awareness that resilient cities depend on inclusion and equality. New York is a striking example: its essential workers in keeping the city running have also been exposed as its most vulnerable, denied essential services themselves due to systemic inequalities – with nearly 80% Latino or African American.

Building urban resilience therefore means investing in those neighbourhoods and communities where people are most at risk, and making equality and diversity foundational premises for urban development. The first recommendation of the UN Secretary-General’s Policy Brief for COVID-19 in the Urban World is to tackle inequalities and safeguard social cohesion, prioritising the most vulnerable.

Process is key

Inclusive outcomes depend on inclusive approaches. One feature of the global response to COVID-19 has been a rise in non-democratic action on the part of governments. As a result, we’ve seen tussles between cities and states, and also between states and citizens, particularly in Europe – with public demonstrations and falling support for government actions. Where support for interventions falls, so does their efficacy, as people flout social distancing measures.

In democracies, swift and effective action therefore demands a degree of co-creation and consensus-building through sustained collaboration and consultation. But the answer is unlikely to be as simple as decentralised decision-making, if we want to unlock exchange and mobility.

How to balance personal freedoms with collective safety is a thorny question, particularly across borders and different political systems. The success of some non-Western countries, such as China and Singapore, in countering the pandemic has depended on tight restrictions monitored through a combination of tagging, facial recognition software, public temperature monitoring and track-and-trace apps.

Rather than speeding towards single solutions, can we take time to reflect on different approaches, keeping an open mind as we observe the push and pull of shifting social and political dynamics? Fear often causes us to close our minds to difficult questions. Perhaps keeping them open is the most important factor in the future of cities.

Suggested reading:

Community-led futures is a radical act

by James Goodman

Join discussion